Pedagogical Goals

This project aims to develop authentic deep learning experiences that incorporate material objects in peer learning and problem solving activities. The importance of experiential learning has been central to constructivist pedagogical practices for nearly a century. Unlike a transactional method of education in which teachers deposits information in the minds of passive learners (what Paulo Freire termed the “Banking Model” of education), constructivist learning is centred on the premise that “knowledge cannot be transmitted but must be constructed by the mental activity of learners” (Michael 2006, 160). Learning is attained through mentally (and often physically) engaging work that allows students to think, and in particular, problem solve. The goals of this learning transcend the lower cognitive objectives of remembering declarative knowledge and focus on procedural learning centring on the higher cognitive levels (Michael 2006; e.g., Application, Analysis, and Evaluation in Bloom’s Taxonomy).

Active learning is deemed “authentic” when the activities undertaken recreate the practices engaged in by professionals in the field (Stein et al. 2006). Phenomenographic teaching philosophy extends this definition of authentic learning to that which meaningfully connects to the understandings and experiences of the learners, situating the learning in the context of the students’ lived experiences (Stein et al. 2006, 240). This student-centred view understands that “the learner’s perspective determines what is learned, not necessarily what the teacher intends should be learned” (Biggs and Tang 2011, 22-23). This informs more holistic teaching methods that centre on the learner (the “Learner Paradigm”, Barr and Tagg 1995) and their “induction into communities of practice” (Stein et al. 2006). A central tenet of learner-centred teaching is the incorporation of collaborative learning. Educational and psychological research has demonstrated that students “learn better when working with others” (Michael 2006, 161; also Bain 2004). Group work, and in particularly peer learning, elevate the deep learning experiences of students (Brown et al. 1988).

Modules

Objects are incorporated into daily lectures and class discussions in order to activate different modes of learning and to enrich conversations around topics such as looting, the loss of archaeological context, and threats to cultural heritage. Printed objects are also used in two learning modules, outlined below. Additional learning modules are currently in development.

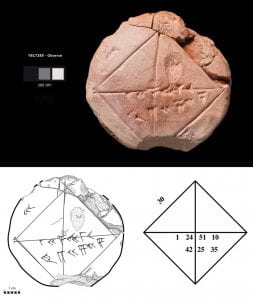

Module 1 – The Development of Writing

This activity module follows a class lecture on the invention of writing. We discuss the first uses of writing in Mesopotamia, from tokens and seals to script, as well as the development of writing elsewhere in the ancient world (including Egypt, China, and the Americas). During the lecture students have the opportunity to handle seals and sealings and tablets with script. The form of early scripts are outlined including pictograms, logograms, and phonemes, and the rebus principle is explained. Students are also shown short videos demonstrating the writing of cuneiform. The objects continue to circulate during this time. The activity follows this introduction.

Activity: Students are broken into groups of approximately 4–6. The students then develop their own rebus-based system using drawn pictograms or emojis. With this writing system the groups are asked to produce three phrases that state: the title of a popular film, a famous US landmark, and a common phrase/cliché (the activity worksheet can be found HERE). This part of the activity takes approximately 10–15 minutes. We then come together as a class to examine and spend approximately 10 minutes attempting to decipher some of the phrases produced by the groups. We conclude the exercise with a 10 minute reflection discussion on the activity and the challenges faced by historians who study ancient texts.

Module 2 – The Study of Coins

This module includes a class lecture on the study of coins in Late Republican and Imperial Rome (earlier classes discuss coinage in Classical and Hellenistic Greece). We overview the study of coins, the importance of numismatic research in studying ancient economies, and the connection between symbols and propaganda. During class students have the opportunity to handle different replica coins. A detailed publication of this module, its learning objectives, and assigned materials can be found in the Visualizing and Materializing Objects: 3D Printed Coins Assignment (Johnston et al., 2022).

Activity: Students are broken into groups of approximately 4–6. Students are first asked to describe and draw one American coin from memory. Each group of students is then provided with a collection of 3–5 coins from different periods of antiquity. The accompanying activity handout includes drawings of both sides of each coin, and epigraphic alphabets for both Greek and Latin (the activity worksheet can be found HERE). Students are then tasked with analyzing the imagery and text on the different coins in their collection. This part of the activity takes approximately 15 minutes. The class then comes together to discuss the results of the analysis. We spend approximately 10 minutes discussing group results and reviewing the drawings of US coins from memory. We conclude the exercise with a 5 minute discussion reflecting on the activity and the challenges faced by historians who study ancient coins.

References

Bain, K. 2004. What the Best College Teachers Do. Cambridge: Harvard.

Barr, R.B., and J. Tagg. 1995. “From Teaching to Learning: A New Paradigm for Undergraduate Education.” Change 27(6): 12–25.

Biggs, J., and C. Tang. 2011. Teaching for Quality Learning at University: What the Student Does, 4th ed. New York: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A. & Duguid, P. 1988. “Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning.” Educational Researcher 18(1): 32–42.

Michael, J. 2006. “Where’s the Evidence. That Active Learning Works?” Adv Physiol Educ 30: 159–167.

Stein, S.T., G. Isaacs, and T. Andrews. 2006. “Incorporating Authentic Learning Experiences within a University Course.” Studies in Higher Education 29(2): 239–258.