American Environmentalism: Washing Away the White Men

This quarter, graduate students enrolled in ENVS 597: Power, Privilege, and the Environment are writing short responses emerging from readings and/or discussions in class.

American Environmentalism: Washing Away the White Men

By: Andy Basabe

Critically analyzing America’s environmental history from the 1800’s to today can be challenging. Critical analysis challenges oneself to deconstruct environmental acts, opinions, essays, policies, laws, and ideologies. Our imagination for what the environment stands for encompasses much more than literary works humans have created. Perhaps environmentalism is related to everyone and everything, and that humans today and humans in the past have always struggled with perceiving everyone’s values and beliefs that come from the environment.

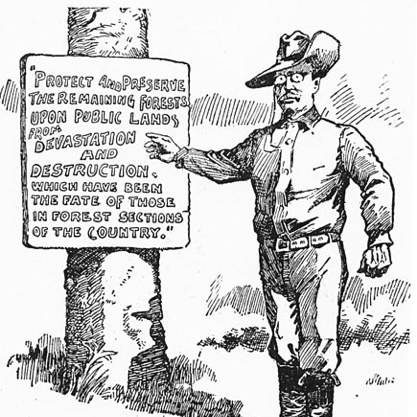

In Power, Privilege, and the Environment, we looked at a selection of historical environmental writers (Grant, Osborn, Sanger, Ehrlich, Vogt) whose discusses that the environment has historically been a place for white men. Those men disregarded the homes of Native Americans, especially during the creation of National Parks, and have only thought about the needs and space for white men. The space was a necessity to re-invigorate themselves by hunting large animals, and exercising their manly instincts. The authors also discussed eugenics in a positive light — relating eugenics to nature, drawing on the survival of the fittest mentalities. How does their work impact current perspectives and representation in natural, outdoor spaces today?

While conceited, destructive, and genocidal in historical/present practice, the idea of protecting land from exploitative economic interests within the modern economic system has prevented a lot more destruction. How do we throw out the bathwater (white men’s ideals of their own lofty relationship with nature, and thus the need to protect it for themselves at the cost to others) and keep the bucket (large tracts of land that provide opportunities for growth, education, and empowerment protected from exploitative economic interests)?

Many issues stem from the dominate Western narrative. Any different culture or life existence that does not fit within the white man’s box is considered “abnormal” and sometimes “savage”. Modern day examples are gender fluidity, disability, and ethnicity, have all received backlash and disapproval from the dominant white man. One of the most obvious examples is the displacement of Native American people; however, many others have also been negatively affected by the good Christian attitude. Anyone who’s identity does not mirror the traditional white man bears an unfair burden of centuries of dominant values.

Eli Clare, as described in Sarah Jaquette Ray’s “The Ecological Other,” lives a life that challenges that dominant narrative. Men like Madison Grant would champion people like Reinhold Messner or Boytek Kurtyka, who are able white men with European ancestry. Claire is transsexual, queer, and disabled. Clare challenges the belief that only “normal” people enjoy nature. His biggest struggle is simply living within “normal” society that constantly challenges him, and that he constantly pushes against. He describes his challenge as a mountain — something he must constantly conquer and climb. His mountain is not something he seeks out, as did Messner and Kurtyka, but a product of social creation.

However, when Clare went to the physical mountain, Mt. Adams in Washington, he sought out the mountain experience. He battled with his internalized social constructions of what he should or should not be, and how his success or failure in the mountains would confirm or deny those beliefs. He describes a state of “post-revolution when the mountain is stripped of the associations glorifying independence, fitness, and transcendence, and then he will be able to accept his bodies limitations as neither tragic nor heroic.” (Ray, 2013. Embedded quotations in italics.) Clare works to connect with nature more inclusively, in a way that starts from the body, not from the mountain. Clare states “I will never find home on the mountain, rather home starts here in my body.”

Transitioning from the dominate narrative to those like Eli Clare, we see a change in ways to engage with nature. Nature becomes about experiencing the world through a body, and that experience is the most important part; however, the efforts and willpower of the men who crafted the system exist no matter what. Mount Adams, the mountain the Clare climbed, is located on U.S. Forest Service land — an legacy of America’s white supremacist, environmentalist past.

The revolution Clare speaks of, moving away from the dominant man/nature narrative, is how the bathwater can get thrown out while we still keep the bathtub. Nature, or the environment, wherever it may be found, can be enjoyed for what it offers to the individual. It is a place where social constructions can disappear. Clare’s recognized that his own experience was empowering, and it helped him to know himself. As Voytek Kurtyka wrote of the value of his time in the mountains: “Whenever a climber leaves the known paths, he enters an area without rules or routines… The only advice comes from deep inside the self.”

In today’s world, sentiments stemming from the eugenics movement exist. Social norms that are harmful to many people exist. Nature as it is recognized by dominant culture is primarily visited by white people. However, nature, in all its forms, has something to offer everyone, and access to “nature” is a legacy of ignorant white men. Can people celebrate the bucket without wanting to muck around in the water? Can the bucket be improved upon to make it welcoming to people of all intersectionalities?

Purdy, Jedidiah (2015, August 13). Environmentalism’s Racist History | The New Yorker.

Ray, S. (2013). The Ecological Other: Environmental Exclusion in American Culture. University of Arizona Press. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.library.wwu.edu/stable/j.ctt1814fw7

Sasser, J. (2014). From Darkness into Light: Race, Population, and Environmental Advocacy. Antipode, 46(5), 1240–1257. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12029