Author Archives: laffrado

The Role of Digitized Newspapers in the Ella Higginson Recovery Project: Dr. Laura Laffrado for the Readex Report

Posted onBy Moira Stockton, Research Assistant

Dr. Laura Laffrado’s recent essay about the role of digitized newspaper databases in literary recovery projects in the Readex Report.

Dr. Laura Laffrado, Director of the Ella Higginson Recovery Project, is featured in the latest issue of the Readex Report. After using Readex’s Early American Newspapers database, a digital archive featuring national and local newspapers, Dr. Laffrado found two previously unrecovered poems by Ella Higginson. The poems were written early in Higginson’s career and were not widely circulated.

In the Readex Report, Dr. Laffrado explains her work with resources such as the Early American Newspapers database in locating Higginson’s writings. Dr. Laffrado has catalogued over 800 Higginson pieces from physical and digital archives. Laffrado writes, “This recent availability of digitized American newspapers with varying circulations and from all U.S. geographical regions has opened unique possibilities for discovering lost works and references.”

The earliest of the two new poems, “Just Once,” appeared in the Daily Nebraska State Journal on October 21, 1888.

If we, who never met, should meet,

And, after meeting, come to know

That, if we had but sooner met,

We might have loved each other so;

If, after meeting many times,

The thought should swell into regret

That God had not ordained it so,

That we in freedom could have met;

If, looking in each other’s eyes—

The while both knew the same sweet care,

And all but passion—conquered—we

Should read the same thought written there;

If, knowing, then, that we must walk

Henceforth in ways as far apart

As sea to sea, because we saw

What trembled in each other’s heart;

Then, if but for one single time,

Well knowing, too, that it was wrong,

Our lips should meet in one last kiss,

Replete with passion, tender, long;

Would this, I say, be sin so black—

Let those all sinless cast the stone—

That a whole blameless after life

Could never for it quite atone?

The second poem, “O, Puget Sound,” appeared in the Tacoma, Washington publication Every Sunday on September 13, 1890.

O, Puget sound that sparkles at my feet,

How soft thou art! How pure, and cool, and sweet!

One great, red poppy in the sunset’s sheen,

The sky above, the golden haze between—

Sunbeams and moonbeams on they bosom meet.

Thou proudly bearest many a white-winged fleet

Upon thy channel’s quiet, peaceful street,

And purple skies to kiss thee ever lean—

O, Puget sound!

Care that would rack my bosom canst cheat

Canst cool and quiet passion’s restless heat:

And when I stoop to thy arms, soft and green,

I feel thy kisses thrill with rapture keen,

And my sad heart with thy heart, passionate beat

O, Puget sound!

To read about Dr. Laffrado’s fascinating work on the Ella Higginson Recovery Project in digital newspaper archives, follow this link:

https://www.readex.com/readex-report/value-digitized-newspaper-collections-researching-neglected-womens-writing-two-newly?cmpid=RDX.RDXRPT

🍀

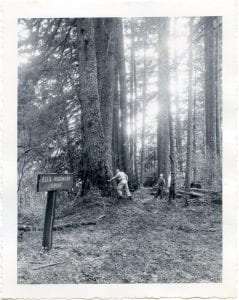

Ella Higginson Grove in the Federation Forest State Park

Posted onBy Moira Stockton, Research Assistant

Photo credit: Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission #35.0.2010.2.2 Date: currently undetermined.

In Federation Forest State Park in Enumclaw, Washington, a special grove of trees is dedicated to Ella Higginson. The Ella Higginson Grove is on land donated in 1952 by Higginson’s closest friend, Catherine Montgomery.

Photo credit: Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission #35.0.2010.2.3 Date: currently undetermined.

Two photos of the grove were sent to Dr. Laura Laffrado, Director of the Ella Higginson Recovery Project, after her op-ed about Higginson’s thoughts on the overdevelopment of the Pacific Northwest appeared in the Seattle Times. To read Dr. Laffrado’s op-ed, click this link: https://virtualmocassins.com/ellahigginson/2019/02/24/laments-over-unbridled-growth-in-our-beloved-northwest-are-nothing-new-dr-laura-laffrado-for-the-seattle-times/

An unidentified newspaper reports in January 1952 on the grove’s establishment, “This transaction has been completed recently by the way of a gift from Miss Catherine Montgomery, a retired faculty member of the Western Washington College of Education. One of the factors of a close friendship between these two distinguished women was their shared love of the Northwest’s beautiful outdoors.”

The article continues, “The newly acquired Ella Higginson Grove adjoins the Federation Forest on the east side, and has some frontage on the transcontinental highway, with close proximity to the White river which borders the south side of the whole park. This grove will prove a valuable and important addition to the park, not only in its beauty, but from an historic standpoint, as the old Naches Trail, a favorite of early pioneers, enters the park at the Higginson Grove boundary.”

Catherine Montgomery. Image courtesy of the Pacific Crest Trail Association. Source: https://www.pcta.org/2017/mother-pacific-crest-trail-catherine-montgomery-48060/

Catherine Montgomery was born on Prince Edward Island in 1867. She moved to Bellingham, Washington in 1899 to accept a position as one of the founding faculty members of what would become Western Washington University. Higginson and Montgomery were close friends until Higginson’s death in 1940. When Montgomery died in 1957, she left her entire estate to the Federation Forest Park. Her estate was eventually used to construct the Catherine Montgomery Interpretive Center.

Montgomery is remembered for proposing the idea of the Pacific Crest Trail in 1926. To read more about her involvement in the Pacific Crest Trail’s beginnings, see “Meet the mother of the Pacific Crest Trail”: https://www.pcta.org/2017/mother-pacific-crest-trail-catherine-montgomery-48060/

Federation Forest State Park exists today because of the admirable efforts of members of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs of Washington, formerly known as the Washington State Federation of Women’s Clubs. Jeanne Caithness Greenlees, former president of the Snohomish district of the Federation, was a timber conservationist who proposed the idea of the park to Esther Maltby, the sixteenth state president of the Federation. Maltby and Helen Sutton, who also served as a state president, worked together on the park’s dedication, which took place in 1949. To learn more about the history of Federation Forest State Park, watch this video produced by the Federation:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YG5z__oU5Yc

To more about the General Federation of Women’s Clubs of Washington State and how to get involved, visit their site at: https://www.gfwcws.org/

🍀

“Laments over unbridled growth in our beloved Northwest are nothing new” – Dr. Laura Laffrado for the Seattle Times

Posted onBy Moira Stockton, Research Assistant

An op-ed in the Seattle Times by Dr. Laura Laffrado, Director of the Ella Higginson Recovery Project and professor of English at Western Washington University, discusses development of the Pacific Northwest, particularly the Seattle area, through the words of an Ella Higginson essay “The New West” published in 1892.

“She [Higginson] could not have imagined the immense population of the region today and what would be needed to support such massive growth. But she rightly feared the changes to come,” Laffrado writes.

To read the full article, click the link below:

🍀

Ella Higginson Celebration Taping Now Available!

Posted onBy Moira Stockton, Research Assistant

On November 2, 2018 a reception was held in honor of the unveiling of the bronze bust of Ella Higginson in Wilson Library at Western Washington University. Film crew Talking to Crows was present to record the event. The edited video has been released for public viewing!

The reception featured speeches from Dr. Laura Laffrado, Director of the Ella Higginson Recovery Project; Dr. Mark Greenberg, Dean of Libraries; Professor Elizabeth Joffrion, Director of Heritage Resources at Western Libraries; and Dr. Brent Carbajal, Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs.

Guests witnessed an exceptional vocal performance by artist Olivia Pedroza, who performed three of Higginson’s poems that had been set to music. Pedroza’s performance starts at 36:04 in the taping of the reception.

To watch the video on YouTube, as well as other Ella Higginson videos: https://youtu.be/Uf3tIGqiho8

To watch the video on Vimeo.com: https://vimeo.com/309681607/249eb76107

To learn more about the film company Talking to Crows, visit their site: https://www.talkingtocrows.com/

Bronze bust of Ella Higginson in Wilson Library, created by Matthew Glenn.

Guests at the reception, November 2, 2018. Photo by Rhys Logan, Western Washington University.

Dr. Laura Laffrado, Director of the Ella Higginson Project, speaking at the reception. Photo by Rhys Logan, Western Washington University.

Olivia Pedroza, Western Washington University Vocal Performance major, who performed three of Higginson’s poems that had been set to music. Pedroza’s performance in the video starts at 36:04. Photo by Rhys Logan, Western Washington University.

Society for the Study of American Women Writers awards Dr. Laura Laffrado for book on Ella Higginson

Posted onBy Moira Stockton, Research Assistant

Dr. Laffrado with her award winning book Selected Writings of Ella Higginson and the plaque given to her by the Society for the Study of American Women Writers for winning the 2018 Edition Award.

Dr. Laura Laffrado, Director of the Ella Higginson Recovery Project, received the Society for the Study of American Women Writer’s (SSAWW) Edition Award for her book Selected Writings of Ella Higginson (2015) at the SSAWW conference in Denver, Colorado on November 10, 2018. Of the Edition Award, the SSAWW website reports, “The SSAWW Edition Award is given every three years at the Society for the Study of American Women Writers’ conference in order to recognize excellence in the recovery of American women writers.”

The plaque given to Dr. Laffrado by the Society for the Study of American Women Writers for winning the 2018 Edition Award.

Below is a transcription of Dr. Laffrado’s acceptance speech. To watch the speech, follow this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t0j324aXdao&list=PLeTs8k1yGXek0EXLHXc1SQcDkQ7j9EiNg&index=3&t=0s

Dr. Laura Laffrado: I promise I will keep this brief. I am utterly, utterly delighted by this, and especially delighted that this award comes from an an organization so dear to my heart, the Society for the Study of American Women Writers. I think I can safely say that the last time Ella Rhoads Higginson’s name would have been publicly proclaimed in the great state of Colorado would have been at the turn of the twentieth century, at the peak of her fame. This would have been around the same time that a review in the Chicago Tribune of her latest book of short stories described her as the author “who put the Pacific Northwest on the literary map.” That was an accurate assessment. Higginson would publish over eight hundred works in her lifetime—I catalogued all of them—she was the recipient of a variety of national literary awards, her poems were set to music and were sung by the major dramatic singers of the day such as Enrico Caruso, and she was elected first Poet Laureate of Washington State. Despite all that, for reasons that every single person in this room understands, she was completely erased from the literary record, pretty much without a trace. It has been one of my pleasures in recovering Ella Higginson to find her self-designed gravestone, a gravestone she designed long after she had been forgotten, on which she had had engraved, “Ella Higginson, Poet – Writer,” just waiting for the moment when sometime in the future she would be found and recovered. I would like to thank the organizers of this wonderful conference. I know how many moving parts there are in a thing like this, and this has been just such a deep pleasure. I would like to close by reading a poem, if you will, by Ella Higginson celebrating her beloved Pacific Northwest, the region with which her writing is most closely associated. This is “The Snow Pearls” from 1897:

I love the pale green emerald,

The ruby’s drop of flame,

The rare and precious sardonyx

Of deeply envied fame;

I love the opal’s restless fire

With green lights interwove,

And e’en the royal amethyst,—

But most of all I love

The string of snow-pearls set around

This great blue sapphire, Puget Sound.

The modest garnet, finely cut,

Gleams like some rich old wine;

I hold the diamond’s crimson flash

As something half divine;

The turquoise—chill December’s gem—

Blue as the blue above,

Is precious unto every heart—

But more than these I love

The string of snow-pearls linked around

This cool, blue sapphire, Puget Sound.

When up Mount Baker’s noble dome

Struggles the morning sun,

And waves of crimson and of gold

Across the pale sky run;

When every fir-tree flashes out

Like a tall gilded spire,

Sweet as a hope rooted in Heaven,

Springs a soft, sudden fire

Upon the snow-pearls strung around

This deep blue sapphire, Puget Sound.

Take, then, all the jewels of the earth

Which only gold can buy—

Not one is worth that glistening chain

Linked in God’s pale green sky!

Let him who will, roam East or West,

On prairie or on sea,

Searching for empty gems—but oh!

Let us contented be

With these pure snow-pearls clasped around

Our own blue sapphire, Puget Sound.

🍀

Ella Higginson’s Bronze Bust Unveils!

Posted onThe bronze bust of Ella Higginson. Photo by the Ella Higginson Blog.

The bust of Ella Higginson has been unveiled!

At 11:30AM Friday November 2nd, the bronze bust of Ella Higginson was installed in the North foyer of Wilson Library at Western Washington University.

Matt Waldman from Western Washington University’s carpentry shop prepares to install the bust. Photo by the Ella Higginson Blog.

From left to right, Pat Schuette and Matt Waldman from the university carpentry shop, and Matt Glenn of BIG Statues in Provo, Utah. Photo by the Ella Higginson Blog.

The reception for the bust took place that afternoon in the Wilson Library Reading Room. Students, staff, faculty, and passionate community members flooded the Reading Room to celebrate with speeches, live music, and free food! Also present were two of Russell Carden Higginson’s (Ella Higginson’s husband) great-great-great nephews representing the Higginson Family.

The great-great-great nephews of Russell Carden Higginson, Russell and Tom. Photo by Debrah Hansen Dorr.

The event was filmed by local filmmakers Talking to Crows, who filmed Higginson’s lost feminist screenplay Just Like the Men this summer. We’ll announce when the unveiling footage becomes available to the public, which we are told will be in about three weeks. To read more about these innovative and vibrant filmmakers, visit their site: https://www.talkingtocrows.com/

Guests in the Reading Room. Photo by Rhys Logan, Western Washington University.

The life-size-and-a-half, hollow-cast bronze bust was sculpted by Matt Glenn in his studio in Provost, Utah. Glenn’s company, BIG Statues, provides bronze sculptures for memorials and parks all over the US. One of Glenn’s recent projects was a memorial for women veterans installed in Las Cruces, New Mexico. To read more about Matt Glenn’s work, visit https://www.bigstatues.com/

Dr. Laura Laffrado, Director of the Ella Higginson Recovery Project, and Matt Glenn of BIG Statues in Provo, Utah with the bust of Ella Higginson. Photo curtesy of Western Libraries, Western Washington University.

The first to speak was Dr. Mark Greenberg, Dean of Libraries, who welcomed guests into the Mabel Zoe Wilson Library. He noted the beautiful friendship that spanned three decades between Mabel Zoe Wilson and Ella Higginson. Next to speak was Elizabeth Joffrion, Director of Heritage Resources, who described the lively research relationship between Dr. Laura Laffrado, Director of the Ella Higginson Recovery Project, and the resources in the Center for Pacific Northwest Studies. Dr. Brent Carbajal, Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs, affirmed Western Washington University’s support for the preservation of women’s achievements in our current political climate. Finally, Dr. Laura Laffrado took the podium to paint a picture of Ella Higginson’s life, from her family’s trek from Kansas to Oregon, her arrival in Whatcom, her first big literary breaks, her international fame, her obscurity after WWI, and now her literary recovery. The last speaker was Dr. Laffrado’s research assistant, Marielle Stockton, who demonstrated Ella Higginson’s love for the people of Whatcom County with a brief survey of her memorial poetry.

Dr. Mark Greenberg, Dean of Libraries. Photo by Rhys Logan, Western Washington University.

Elizabeth Joffrion, Director of Heritage Resources. Photo by Rhys Logan, Western Washington University.

Dr. Brent Carbajal, Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs. Photo by Rhys Logan, Western Washington University.

Dr. Laura Laffrado, Director of the Ella Higginson Recovery Project. Photo by Rhys Logan, Western Washington University.

Talented Vocal Performance music major Olivia Pedroza of Sedro-Woolley then performed three songs, each of them featuring Ella Higginson poems as lyrics that were performed regularly in Higginson’s own lifetime. Footage of Pedroza’s marvelous performance will be available shortly; a special thanks again to filmmakers Talking to Crows. Next, Pedroza will be performing in WWU’s Concert Choir’s program “A Light in the Darkness: Songs of Hope and Comfort” on November 17, 2018. For more information on the event, visit here: https://cfpa.wwu.edu/event/light-darkness-songs-hope-and-comfort

Olivia Pedroza, Vocal Performance major. Photo by Rhys Logan, Western Washington University.

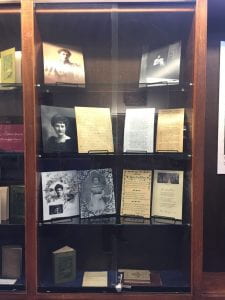

The brilliant manager of Special Collections, Tamara Belts, curated the first ever Ella Higginson exhibit. Pieces from the Center for Pacific Northwest Studies, Dr. Laffrado’s, and her research assistant’s collection were featured. Belts also put together a large binder of newspaper clippings about Higginson, postcards featuring Higginson’s poems, and sheet music where Higginson’s poems were used as lyrics. Included was Ella Higginson’s music score cabinet, donated by former university Children’s Literature librarian Miriam B. Snow Mathes.

The music score cabinet of Ella Higginson, kept in Special Collections in Western Libraries. Photo by the Ella Higginson Blog.

Cases from the Ella Higginson exhibit by Tamara Belts. Photos by the Ella Higginson Blog.

“What a deep pleasure it was to join with the many friends of Western who packed the Library’s Reading Room on Friday for the gala Ella Higginson Celebration!” Dr. Laffrado said of the reception. “Over a century after the peak of her fame, Ella Higginson is now permanently memorialized in a beautiful bronze bust proudly displayed in the entrance to Wilson Library. This is a wonderful moment of feminist literary recovery that I am so pleased to have guided.”

The bronze bust of Ella Higginson is now the fifth public statue of a female historical figure in Washington State, but there are nearly thirty statues of male historical figures in Washington. Your faithful blog editor hopes that the bust of Ella Higginson will inspire the installment of more statues of women to eliminate the gender disparity of historical monuments in Washington.

Dr. Laffrado with the bust before installation. Photo curtesy of Western Libraries, Western Washington University.

Dr. Laffrado sharing a moment with the bust. Photo by the Ella Higginson Blog.

Bronze Bust of Ella Higginson Unveiling at Western Washington University!

Posted onBy Moira Stockton, Research Assistant

As announced earlier this year, a bronze bust of Ella Higginson will be installed in Western Washington University’s Wilson Library. The unveiling will take place on November 2, 2018 in the Wilson Library Reading Room from 4:00PM-6:00PM.

All are welcome to celebrate the literary recovery of the first Poet Laureate of Washington State with us! There are no reservations necessary or admission fees. See an exhibit of Higginson works and artifacts, and enjoy a live musical performance and refreshments.

To read more about the event, read the Western Today’s press release on the event: https://westerntoday.wwu.edu/news/ella-higginson-celebration-at-western-libraries-set-for-nov-2

The Mabel Zoe Wilson Library as seen from the upper floors of Old Main at Western Washington University.

The Reading Room of Wilson Library where the reception of the Ella Higginson bust will take place.

The bust will be placed in the Wilson Library entrance hallway, across from the portrait of the library’s first librarian, Mabel Zoe Wilson.

The Mabel Zoe Wilson Library began construction in 1927, being the first separate library building the State Normal School at Bellingham (now Western Washington University) ever had. Until that time, the library was housed in various rooms and floors (and even in part of the attic) of what is today called Old Main, the only building on campus during the school’s early years. In 1964, this library was named for pioneer librarian Mabel Zoe Wilson, who was the head of the library from 1902 to 1945, an astonishing 43 years of service! Just under two months after the naming, Mabel Zoe Wilson would die at the age of 86.

Ella Higginson and Mabel Zoe Wilson shared a sweet friendship. In 1953, thirteen years after Ella Higginson passed away, Mabel Zoe Wilson donated dozens of letters that Ella Higginson had written to her over several decades to the University of Washington’s Special Collections, all perfectly preserved and including the envelopes. This correspondence reveals a deep and affectionate bond between these two inspiring women. How fitting it is that a bronze bust of Ella Higginson will be installed in one of her dearest friend’s thriving legacy, the Mabel Zoe Wilson Library.

Mabel Zoe Wilson, WWU’s first librarian.

Dear Zoe Wilson. . .

This is just to tell you how much I admire you and how much I love you – so I hope you’ll receive it before you turn homeward. I think of you so often and always with the same constant and loyal affection I feel for Olive – you are so different and yet so alike. I’m sure you’re having a wonderful summer and I think you might have let me tag! . . . If you go to Venice, think of me every single minute – and love me a little bit, bad as I am.

Your devoted friend,

Ella Higginson

From a July 14, 1925 letter to Mabel Zoe Wilson, who was traveling in Rome that summer.

“A Sepulchre of Snow”: Ella Higginson’s Memorialzation of the 1939 Avalanche at Mt. Baker

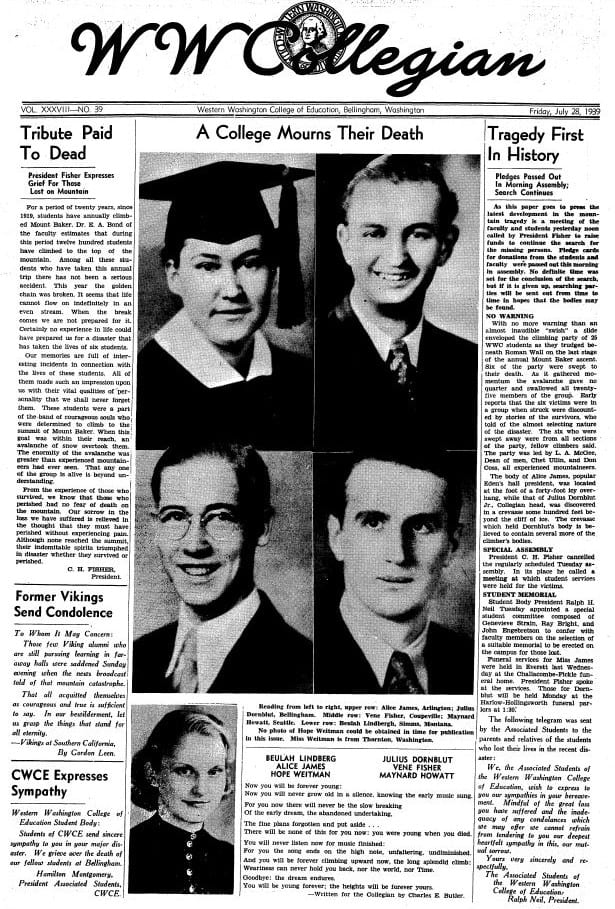

Posted onFront page of the July 28, 1939 Western Washington College of Education student newspaper the WWC Collegian, now titled the Western Front. Digitized by Special Collections, Western Libraries Heritage Resources, Western Washington University.

A local tragedy that took the lives of six young affiliates of Western Washington College of Education (now Western Washington University) inspired one of Ella Higginson’s most touching memorial poems “A Sepulchre

of Snow.”

of Snow.”

Headlines from various newspapers: July 24, 1939 The Bend Bulletin of Bend, OR; July 24, 1939 The Eugene Guard of Eugene, OR; July 24, 1939 The Vidette Messenger of Valparaiso, IN.

On July 22, 1939 a group of twenty-five experienced

mountain climbers were fifteen minutes from the summit of Mount Baker during the 20th annual climb hosted by Western Washington College of Education when an avalanche the width of a football field swept

the entire party a mile down the mountain. The tumbling snow spilled over into

a crevasse in the mountain seventy feet deep. When the slide had ceased, seven

members were missing.

mountain climbers were fifteen minutes from the summit of Mount Baker during the 20th annual climb hosted by Western Washington College of Education when an avalanche the width of a football field swept

the entire party a mile down the mountain. The tumbling snow spilled over into

a crevasse in the mountain seventy feet deep. When the slide had ceased, seven

members were missing.

The two guides of this expedition frantically searched

the vast snowscape and managed to find Elizabeth Beers clinging to the mouth of

the crevasse by her fingertips. Two other members of the party raced down the

mountain and reached William N. Parke, the current district forest ranger at

Mt. Baker, and alerted him of the disaster. Parke immediately gathered both a

rescue team and supplies and initiated a search that would last six days,

hoping to find six bodies. They found two. The body of Alice James and Julius

Dornblut were recovered from the top few feet of snow that filled the crevasse.

It is believed that the remaining victims’ bodies were piled under dozens of

feet of hardening snow in the crevasse near the bottom of the slide.

the vast snowscape and managed to find Elizabeth Beers clinging to the mouth of

the crevasse by her fingertips. Two other members of the party raced down the

mountain and reached William N. Parke, the current district forest ranger at

Mt. Baker, and alerted him of the disaster. Parke immediately gathered both a

rescue team and supplies and initiated a search that would last six days,

hoping to find six bodies. They found two. The body of Alice James and Julius

Dornblut were recovered from the top few feet of snow that filled the crevasse.

It is believed that the remaining victims’ bodies were piled under dozens of

feet of hardening snow in the crevasse near the bottom of the slide.

An unidentified hat and handkerchief were found later,

as well as the glasses of Vene Fisher.

as well as the glasses of Vene Fisher.

Members of the search party surveying the path of the avalanche. Photograph by John Scurlock, July 1939.

At the time, the Mt. Baker avalanche of 1939 became

the worst mountain tragedy in Washington State history. In light of the

disaster, Higginson wrote three poignant and haunting sentences titled

“A Sepulchre of Snow.”

the worst mountain tragedy in Washington State history. In light of the

disaster, Higginson wrote three poignant and haunting sentences titled

“A Sepulchre of Snow.”

Of

all beautiful burial places on this lovely earth, if I might choose my own, my

choice would surely be to lie in the depths of a crevasse, covered with

perpetual snow; and with my name visibly etched by God upon a majestic mountain

for an enduring monument.

all beautiful burial places on this lovely earth, if I might choose my own, my

choice would surely be to lie in the depths of a crevasse, covered with

perpetual snow; and with my name visibly etched by God upon a majestic mountain

for an enduring monument.

Think

of the sunrises and the sunsets; think of the moonlight on those silvery

slopes; think of how large and brilliant are the stars that keep ceaseless

watch over those silent places.

of the sunrises and the sunsets; think of the moonlight on those silvery

slopes; think of how large and brilliant are the stars that keep ceaseless

watch over those silent places.

Through

the ages to be identified with one of the most beautiful mountains known; to

lie there forever, on the silver crest of the world, close to God—my brothers,

do you know anything lovelier after death than this would be?

the ages to be identified with one of the most beautiful mountains known; to

lie there forever, on the silver crest of the world, close to God—my brothers,

do you know anything lovelier after death than this would be?

On Western Washington University’s campus, at the

north end of Old Main, is a memorial erected in honor of the victims: Julius

Dornblut, Vene Fisher, Maynard Howat, Alice James, Beulah Lindberg, and Hope

Weitman.

north end of Old Main, is a memorial erected in honor of the victims: Julius

Dornblut, Vene Fisher, Maynard Howat, Alice James, Beulah Lindberg, and Hope

Weitman.

The line “You will be forever climbing upward now” is

taken from a memorial poem written by Charles E. Butler, who was the current reference

librarian for the college.

Julius Dornblut was born in Radersburg, Montana on

January 23, 1909. He received his BA from Western Washington College of

Education in 1935. For the past four years he had taught at Alderwood Manor in

the Edmond’s school district. At the time of his death, he was fulfilling the

roles of adviser and editor of the WWC

Collegian and was vice-president of the Alumni Association. He was survived

by two sisters.

January 23, 1909. He received his BA from Western Washington College of

Education in 1935. For the past four years he had taught at Alderwood Manor in

the Edmond’s school district. At the time of his death, he was fulfilling the

roles of adviser and editor of the WWC

Collegian and was vice-president of the Alumni Association. He was survived

by two sisters.

Vene Fisher was born in Brady, Montana on June 21,

1914. The avalanche occurred the day after his twenty-fifth birthday. He

received his BA from Western Washington College of Education in 1936. He taught

for a year in Grays Harbor County, then had been an assistant in the county

engineer’s office of Island County for the past two years. He was survived by

his wife Hazel Lindquist Fisher, his parents, two brothers, and one sister.

1914. The avalanche occurred the day after his twenty-fifth birthday. He

received his BA from Western Washington College of Education in 1936. He taught

for a year in Grays Harbor County, then had been an assistant in the county

engineer’s office of Island County for the past two years. He was survived by

his wife Hazel Lindquist Fisher, his parents, two brothers, and one sister.

Maynard Howat was born in Seattle, Washington on May

3, 1915. He was scheduled to complete his three year degree at Western

Washington College of Education less than a month later on August 18, 1939. A

veteran trackman, Howatt captured a conference title for the two-mile run twice

while attending college. He was survived by his parents, one brother, and one

sister.

3, 1915. He was scheduled to complete his three year degree at Western

Washington College of Education less than a month later on August 18, 1939. A

veteran trackman, Howatt captured a conference title for the two-mile run twice

while attending college. He was survived by his parents, one brother, and one

sister.

Alice James was born in Valley City, North Dakota on

June 3, 1917. While attending Western Washington College of Education, she was

a member of the orchestra and the library student staff. She left the college

halfway through the 1938-39 academic year to teach in Standwood and planned to

return there in the fall. She was survived by her parents, three sisters, and a

brother.

June 3, 1917. While attending Western Washington College of Education, she was

a member of the orchestra and the library student staff. She left the college

halfway through the 1938-39 academic year to teach in Standwood and planned to

return there in the fall. She was survived by her parents, three sisters, and a

brother.

Beulah Lindberg was born in Simms, Montana on October

9, 1916. She attended the State Teachers’ College at Dillon, Montana then

taught in both Belt and Fairfield, Montana. She was visiting friends also of

Montana origin who lived here in Bellingham when she was killed by the

avalanche. She was survived by her parents in her hometown.

9, 1916. She attended the State Teachers’ College at Dillon, Montana then

taught in both Belt and Fairfield, Montana. She was visiting friends also of

Montana origin who lived here in Bellingham when she was killed by the

avalanche. She was survived by her parents in her hometown.

Hope Weitman was born in Prairie City, Oregon on

September 28, 1915. She graduated from Eastern Washington College of Education

in Cheney and had taught in Chewelah. She was attending summer classes at

Western Washington College of Education and was residing at the Bellingham

YWCA. She was survived by her parents.

September 28, 1915. She graduated from Eastern Washington College of Education

in Cheney and had taught in Chewelah. She was attending summer classes at

Western Washington College of Education and was residing at the Bellingham

YWCA. She was survived by her parents.

“A Sepulchre of Snow” printed on a card ca. 1939. Courtesy of Special Collections, Western Libraries Heritage Resources, Western Washington University.

“Under the Bay”

Posted onby Moira Stockton, Research Assistant

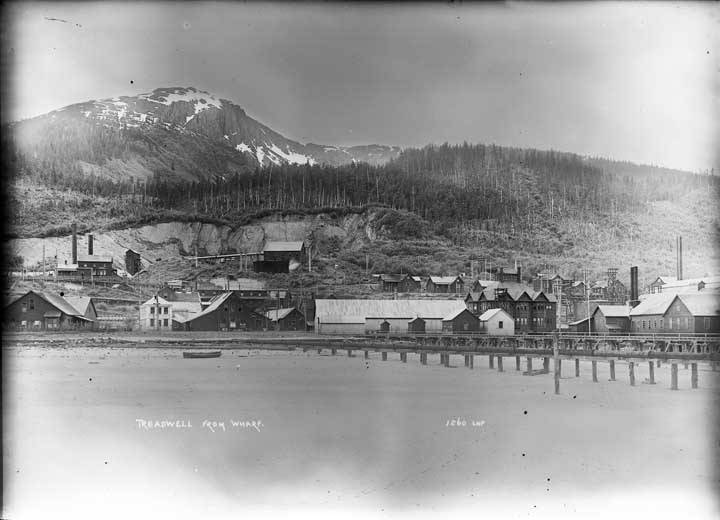

Treadwell and Gastineau Channel in 1899. Image courtesy of the Winter and Pond Collection. Photographs, 1893-1943.

ASL-PCA-87, Alaska State Library.

ASL-PCA-87, Alaska State Library.

There is a fascination in walking through these high-ceiled, brilliantly lighted stopes, and these low-ceiled, shadowy drifts. Walls and ceilings are gray quartz, glittering with gold. One is constantly compelled to turn aside for the cars of or on their way to the dumping places, where their burdens go thundering to the levels below. (Page 125 of Alaska, the Great Country by Ella Higginson, 1908)

In 1908, the prestigious Macmillan Company published Ella Higginson’s book Alaska, the Great Country. A mix of Native American cultural observations, territorial history, landscape description, and travel anecdotes, Alaska, the Great Country is a fascinating book. In the tenth chapter, Higginson recounts her experience touring America’s largest goldmine:

Our captain obtained permission to take us down into the mine. This was not so difficult as it was to elude the other passengers. At last, however, we found ourselves shut into a small room, lined with jumpers, slickers, and caps. Shades of the things we put on to go under Niagara Falls! “Get into this!” commanded the captain, holding a sticky and unclean slicker for me. “And make haste! There’s no time to waste for you to examine it. Finicky ladies don’t get two invitations into the Treadwell. Put in your arm.”

My arm went in. When an Alaskan sea captain speaks, it is to obey. Who last wore that slicker, far be it from me to discover. . . “Now put on this cap.” Then beheld mine eyes a cap that would make a Koloshian ill. “Must I put that on?” I whispered it, so the manager would not hear. “You must put this on. Take off your hat.” My hat came off, and the cap went on. It was pushed down well over my hair; down to my eyebrows in the front and down to the nape of my neck in the back.

“There!” said the captain, cheerfully. “You needn’t be afraid of anything down in the mine now.”

Alas! there was nothing in any mine, in any world, that I dreaded as I did what might be in that cap.

Treadwell opened in 1882 on Douglas Island, across the Gastineau Channel from Juneau. Between 1882 and 1922, Treadwell produced $70 million dollars in gold, just over $176 million dollars in today’s money. Accompanied by the manager of the mine (who remains unnamed in Alaska) and Higginson’s friend, Catherine Montgomery (faculty at the Washington State Normal School at Bellingham, now known as Western Washington University), they entered the Treadwell gold mine.

There were four of us, with the manager, and there was barely room on the rather dirty “lift” for us.

We stood very close together. It was dark as a dungeon.

“Now—look out!” said the manager.

As we started, I clutched somebody,—it did not matter whom. I also drew one wild and amazed breath; before I could possible let go of that on—to say nothing of drawing another—there was a bump, and we were in a level one thousand and eighty feet below the surface of the earth.

We stepped out into a brilliantly lighted station, with a high, glittering quartz ceiling. The swift descent had so affected my hearing that I could not understand a word that was spoken for

fully five minutes. None of my companions, however, complained of the same trouble.

fully five minutes. None of my companions, however, complained of the same trouble.

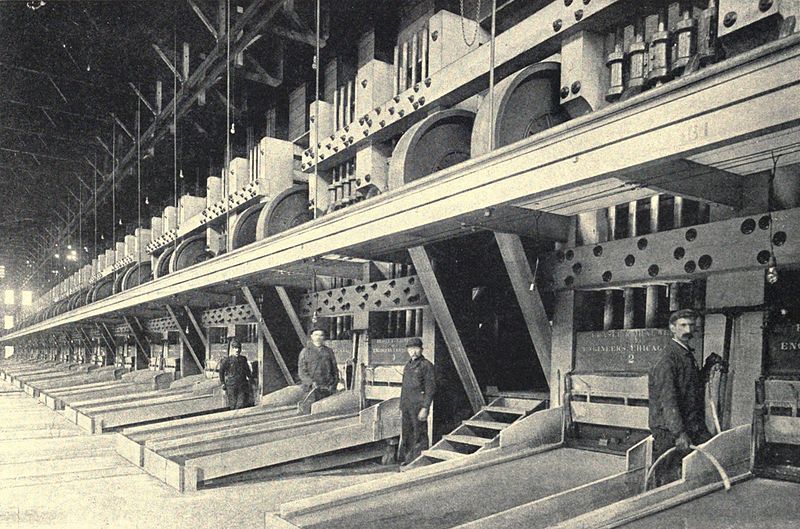

The deepest mine shaft in Treadwell was 2,400 feet below the surface. From these depths, ore (sediment containing valuable minerals or elements) was extracted and then refined in the five Treadwell stamp mills. Treadwell had the most stamps of any mining operation on the continent, housing nine-hundred stamps when Higginson toured it. Stamps are refining machines used to extract gold by crushing the ore. These gargantuan pieces of equipment endangered the lungs of the operators by constantly kicking up microscopic pieces of ore that the operators would inhale. Higginson described the noise of the stamps as

such:

such:

The nine hundred stamps drop ceaselessly, day and night, with only two holidays in a year—Christmas and the Fourth of July. The noise is ferocious. In the stamp-mill one could not

distinguish the boom of a canon, if it were fired within a distance of twenty feet, from the deep and continuous thunder of machinery.

distinguish the boom of a canon, if it were fired within a distance of twenty feet, from the deep and continuous thunder of machinery.

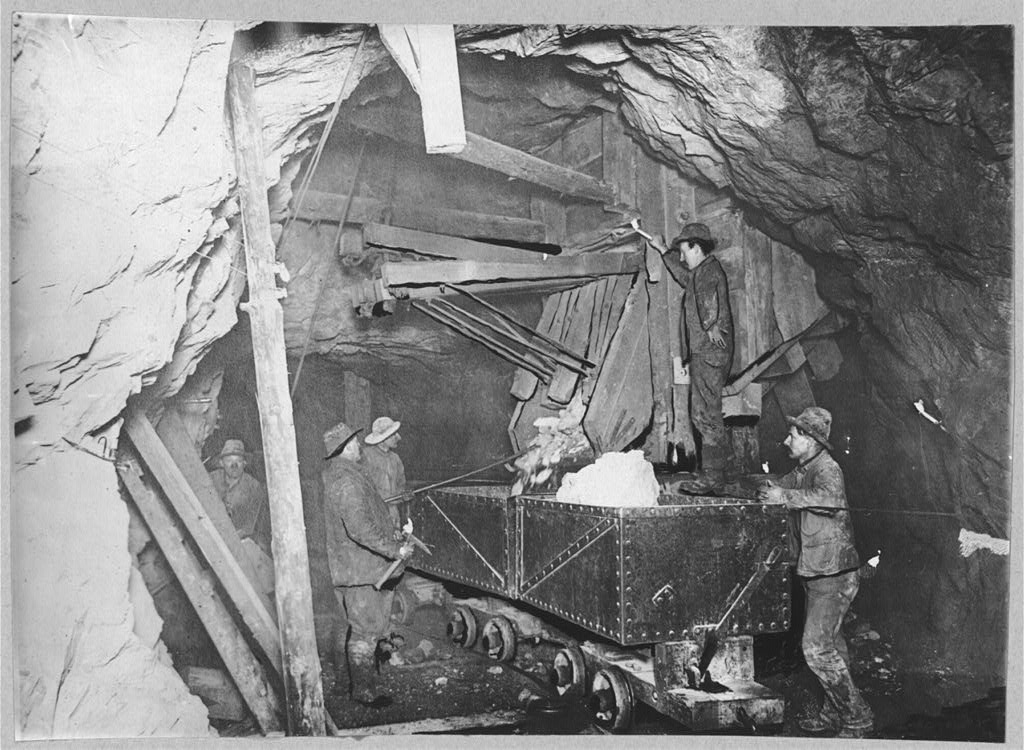

The stamps and operators of Treadwell in 1908. Image courtesy of Through the Yukon and Alaska, Mining and Scientific Press, San Francisco, 1909

Higginson was touring the mine for research for Alaska, the Great Country, and relentlessly questioned the manager:

No one has ever accused me of being shy in the matter of asking questions. It was the first time I had been down in one of the famous gold mines of the world, and I asked as many questions as a woman trying to rent a forty-dollar house for twenty dollars. Between shafts, stations, ore bin, crosscuts, stopes, drifts, levels, and winzes, it was less than fifteen minutes before I felt the cold moisture of despair breaking out upon my brow. Winzes proved to be the last straw. I could get a glimmering of what the other things were; but winzes!

The manager had been polite in a forced, friend-of-the-captain kind of way. He was evidently willing to answer every question once, but whenever I forgot and asked the same question twice,

he balked instantly. Exerting every particle of intelligence I possessed, I could not make out the difference between a stope and a station, except that a stope had the higher ceiling.

he balked instantly. Exerting every particle of intelligence I possessed, I could not make out the difference between a stope and a station, except that a stope had the higher ceiling.

“I have told you the difference three times already,” cried the manager, irritably.

The captain, back in the shadow, grinned sympathetically.

“Nor’-nor’-west, nor’-by-west, a-quarter-nor’,” said he, sighing. “She’ll learn your gold mine sooner than she’ll learn my compass.”

Then they both laughed. They laughed quite a while, and my disagreeable friend laughed with them. For myself, I could not see anything funny anywhere.

I finally learned, however, that a station is a place cut out for a stable or for the passage of cars, or other things requiring space; while a stope is a room carried to the level of the top of the main crosscut. It is called a stope because the ore is “stoped” out of it. But winzes! What winzes are is

still a secret of the ten-hundred-and-eighty-foot level of the Treadwell mine.

still a secret of the ten-hundred-and-eighty-foot level of the Treadwell mine.

Miners work the overhead portion of stope on the 2300 ft. level in Treadwell. Image courtesy of the Harry F. Snyder Photograph Collection: Treadwell, Alaska, 1916-1918. ASL-PCA-38, Alaska State Library.

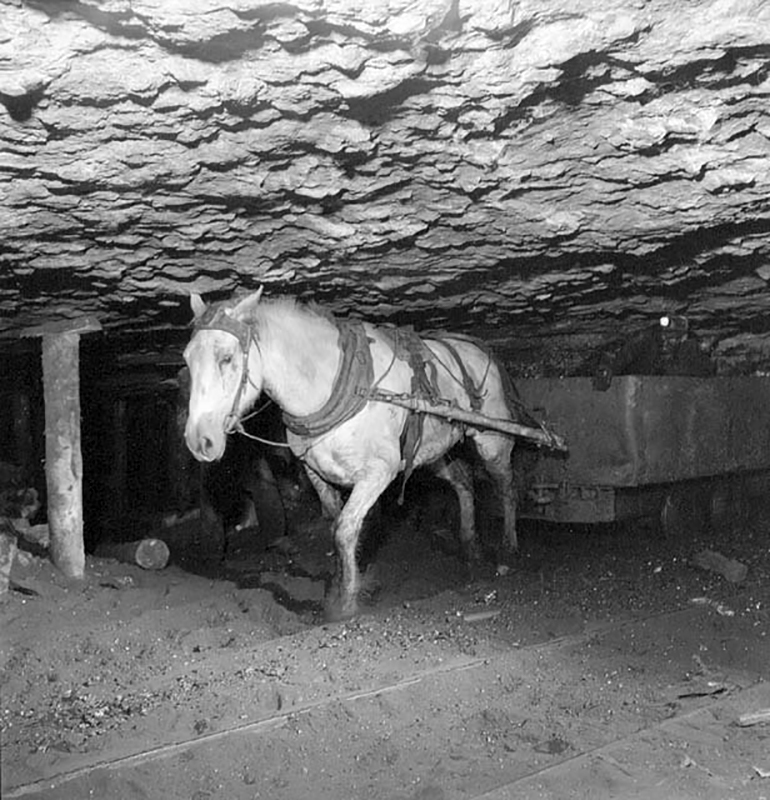

When Higginson toured Treadwell, they were still in the practice of using ‘pit ponies’ to haul tram cars of ore in the mines. Though most American mines that used equestrian labor used donkeys or mules, Treadwell followed the British method of using small horses, usually no more than twelve hands high due

to the low ceilings of the mines.

to the low ceilings of the mines.

A pit pony and miner in a mine at New Aberdeen, NS, in August 1946. Image Courtesy of National Film Board of Canada/Library & Archives Canada/PS-116676.

A pit pony being lowered into a mine. Image courtesy of “Ghosts of the Coal Mines.”

Higginson, a lover of horses herself, clearly was affected by the sight:

Tram-cars filled with ore, each drawn by a single horse, passed us in every drift—or was it in crosscuts and levels? One horse had been in the mine seven years without once seeing sunlight

or fields of green grass; without once sipping cool water from a mountain creek with quivering, sensitive lips; without once stretching his aching limbs upon the soft sod of a meadow, or racing with his fellows upon a hard road.

or fields of green grass; without once sipping cool water from a mountain creek with quivering, sensitive lips; without once stretching his aching limbs upon the soft sod of a meadow, or racing with his fellows upon a hard road.

But every man passing one of these horses gave him an affectionate pat, which was returned by a low, pathetic whinny of recognition and pleasure.

“One old fellow is a regular fool about these horses,” said the manager, observing our interest. “He’s always carrying them down armfuls of green grass, apples, sugar, and everything a horse will eat. You’d ought to hear them nicker at sight of him. If they pass him in a drift, when he hasn’t got a thing for them, they’ll nicker and nicker, and keep turning their heads to look after him. Sometimes it makes me feel queer in my throat.”

A miner and a pit pony, undated. Image courtesy of “Ghosts of the Coal Mines.”

Thanks to later innovations, horses were eventually replaced with mechanical tram cars. The last recorded group of working pit ponies was in Queensland, Australia; they were allowed to retire in 1990.

If you have read Higginson’s poetry, you are well aware of her fascination and devotion to Bellingham Bay, Puget Sound, the ocean, and most all bodies of water. It was here in the Treadwell mine that she experienced water in an entirely different way.

“I suppose,” he said, sighing, “you wouldn’t care to see the—”

I did not catch the last word, and had no notion what it was, but I instantly assured him that I would rather see it than anything in the whole mine.

His face fell.

“Really—” he began.

“Of course we’ll see it,” said the captain; we want to see everything.”

The manager’s face fell lower.

“All right,” said he, briefly, “come on!”

We had gone about twenty steps when I, who was close behind him, suddenly missed him. He was gone.

Had he fallen into a dump hole? Had he gone to atoms in a blast? I blinked into the shadows, standing motionless, but could see no sign of him.

Then his voice shouted from above me—“Come on!”

I looked up. In front of me a narrow iron ladder led upward as straight as any flag-pole, and almost as high. Where it went, and why it went, mattered not. The only thing that impressed me

was that the manger, halfway up this ladder, had commanded me to “come on.”

was that the manger, halfway up this ladder, had commanded me to “come on.”

I? to “come on!” up that perpendicular ladder whose upper end was not in sight!

But whatever might be at the top of that ladder, I had assured him that I would rather see it than anything in the whole mine. It was not for me to quail. I took firm hold of the cold and unclean rungs, and started. When we had slowly and painfully climbed to the top, we worked our way through a small, square hole and emerged into another stope, or level, and in a very dark part of it. Each man worked by the light of a single candle. They were stoping out ore and making it ready to be dumped into lower levels—from which it would finally be hoisted out of the mine in

skips.

skips.

The ceiling was so low that we could walk only in a stooping position. The laborers worked in the same position; and what with this discomfort and the insufficient light, it would seem that their

condition was unenviable. Yet their countenances denoted neither dissatisfaction nor ill-humor.

condition was unenviable. Yet their countenances denoted neither dissatisfaction nor ill-humor.

“Well,” said the manager, presently, “you can have it to say that you have been under the bay, anyhow.”

“Under the—”

“Yes; under Gastineau Channel. That’s straight. It is directly over us.”

A picture of miners in the shaft that extends beneath Gastineau Channel in 1916. Image courtesy of Frank and Frances Carpenter collection, Library of Congress.

This concluded her tour of Treadwell: “We immediately decided that we had seen enough of the great mine, and cheerfully agreed to the captain’s suggestion that we return to the ship.” It remains unknown on which trip to Alaska Higginson went to Treadwell, for she took four tours of Alaska in the years shortly before the publication of Alaska, the Great Country.

“The Treadwell is the pride of Alaska.” Higginson declares in the book. “Its poetic situation, romantic history, and admirable methods should make it the pride of America.”

Douglas Island and Treadwell as seen from Gastineau Channel, c. 1896-1913. Image courtesy of the Paul Sincic Collection. Photographs, ca. 1898-1915. ASL-PCA-75, Alaska State Library.