Chloe Dichter is a photographic artist currently based out of sunny Albuquerque, New Mexico. She received her BFA in photography from Western Washington University and is currently an MFA candidate at the University of New Mexico. Dichter’s practice centers around alternative and analog processes. Fascinated with the pursuit of archiving both memory and artifact, Dichter’s works act as tangible glimpses of histories that belong to both her and family. Much of her work is informed by her culturally Jewish upbringing and the search for ancestral connection.

To see more of her work, check out her website at: https://chloedichter.com/

What first got you into photography? What made you want to pursue it in college?

I got really interested in landscape photography at first, because at the time I had the goal to visit every US National Park (so far I’ve been to 40). I loved taking photo classes in high school and started to branch out by doing highly stylized studio portraits. This was also when I started shooting analog and I just knew it was something I wanted to pursue. It was the first art medium that I felt I could truly express myself in, and I could explore openly. It felt like it was boundless. Photography felt like I could be as weird as I possibly wanted to be – the freakier the better.

What is your creative process?

Right now my practice is heavily reliant on research. A lot of my projects stem from historical, genealogical, and geographical research. Experimentation is also a huge part of my process: being able to work with my hands, be in the darkroom, try out new processes and surfaces is what acts as a launch pad for what the project will become.

What would you say is your philosophy of art making?

I think for me it’s about continuing to push the limits of image-making and being true to myself and my own interests.

What made you want to work with edible or unconventional materials?

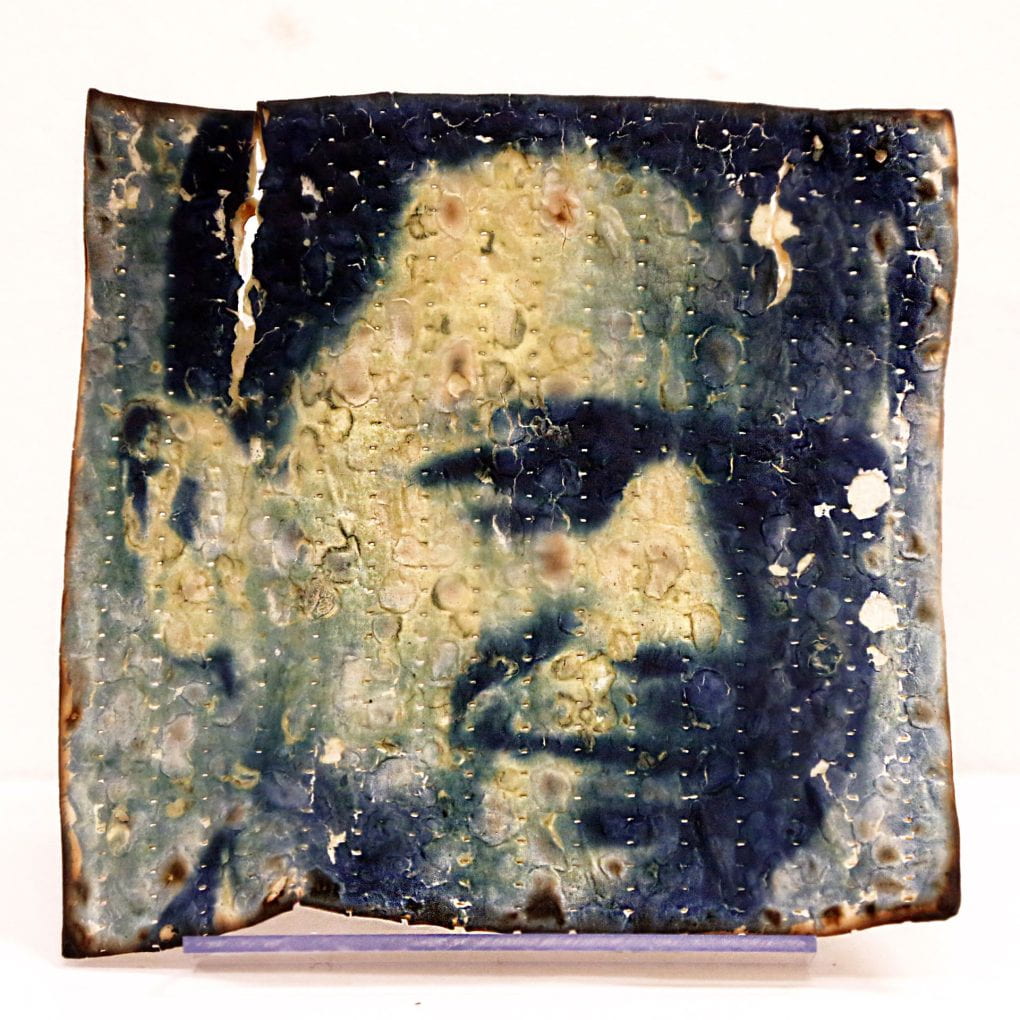

The start of using food as the vehicle for my images was during my BFA year at Western, when I was doing work based on my Jewish culture and family. I had experimented with many different materials to print onto such as canvas, denim, wood, and gauze but I felt I needed a substrate that felt connected to the histories I was exploring so I decided to try my hand at printing onto matzo. It turned out so cool and shockingly worked. I had an image that lived on a cracker. And that’s what started this mayhem of using the grocery store as my art supplier.

What message(s) do you try to send with your pieces?

People, time, memories, and histories will always feel impermanent whether you want to accept it or not. I like to encourage viewers to connect to their own family trees and archives when they look at my work – it’s not just unique to mine. You don’t have to be Jewish to connect to the work, and you can have ownership or at least engage with your family’s history, even if you don’t know a lot about it.

How has graduate school been for you and how have your artistic methods changed since you’ve graduated?

I’m only halfway through my first year, so my methods haven’t changed much. I’ve still continued working in the same processes and my research is still rooted in the same questions that I was looking at during my BFA. I hope it’s gotten a little more sophisticated and complicated.

You print a lot of your work onto food items, so I have to ask, have you ever been tempted to eat some of your work?

If I had a death wish! It would be cool to explore the performative aspect of eating as that’s such an important way I connect to Judaism. But I won’t be eating any chemistry-coated food anytime soon as I would like to graduate. And honestly some of the materials become disgusting as I work on it. Especially the meat – I have a visceral reaction to it as it decomposes. They have more physical and emotional weight as they rot and that definitely affects my appeal towards them in terms of putting them in my mouth.

How does the temporary nature of printing onto food that will eventually rot, change your relationship with your artwork, or change the message behind your artwork?

As artists there is an importance placed on object, especially when you put a lot of time into that object. So working with temporary works, you kind of have to let go of that preciousness and the ownership of it. And that’s what I try to wrap my mind around when I’m working with family stuff. So documentation is really important in my practice, so that at least an iteration of the work can continue to exist when the object no longer does.

How difficult is it to get your photos onto the medium? How long have you been printing onto unconventional mediums? What inspired you to do so?

It all depends on the specific medium. Oddly enough, it feels like the matzo cracker was made for cyanotypes. But other foods, like gefilte fish, or onion skins, or potato are far more involved. For example, after a few tries to no avail of printing on the onion skin, my partner suggested lightly sanding the surface so that it would attach better and it worked. With other foods I have to bake them at a low temperature or blow dry them to dehydrate them. I never thought I’d be saying that I blow dried my gefilte fish. I’d say that the first time I started printing onto unconventional media was when I tried out the matzo crackers. And I would consider “unconventional” in my practice to be the material that isn’t really archivable. So about two or three years now.

Your works titled Skin are described as “cyanotypes on animal and human skin”, is it real human skin and how did you get it? How did you feel printing onto it?

Okay, I have to warn you. This is kind of nasty. Yes, it is real human skin, it’s mine. Have you ever heard of a foot peel? It’s like a little sock with chemicals that make your feet baby soft, and you can get it at Target? Well before you get to that point, all your skin has to shed in sheets. So the skin is from my foot and I had the grotesque impulse to keep the larger pieces so that I could put images onto them. Lo and behold, you can cyanotype onto dead foot skin. It felt like printing onto the onion skin if I’m being honest. I might be more grossed out if it was someone else’s.

Who are the people in these photographs?

Most are images of various family members, both distant and immediate. Some are ancestors that I’ve never met, some are ones I spend holidays with. And now, a lot are of me – I’m starting to explore more self portraiture, but not as direct as a facial portrait. A lot are fragments and body parts that might not be recognizable.

What was your favorite medium to print onto?

It’s hard to answer, because while some I find more visually interesting or successful, they’re the more complicated and frustrating to print onto. There’s something rewarding about getting an image to live on an egg noodle. But I think the matzo remains one of my favorites.

Out of all your pieces you’ve made thus far, which one has been most impactful to you to make?

The eggshells. After it worked, it was like a light went off. And it was fragile – it required extreme care and the most handling since they were displayed for the BFA show. It was also the only time I’ve backlit my work, so it opened the door to trying new ways to display, and I’d never made so many. So I had to participate in a lot of egg-related recipes so that I could get over two cartons to print onto. With my current work using meat, I can really bang that stuff around and it’s fine. You look at those eggshells wrong and it’s all over.

Where do you draw inspiration from your personal life?

Walking into a Jewish deli and immediately hearing an old woman complaining in Yiddish, grabbing a black and white cookie on my way out, along with my entire bag of leftovers. I’m inspired by Passover dinner with my family. I’m inspired by the colorful branding on the containers that a lot of Jewish food comes in as a way to think about American-Jewish identity.

Do you have any advice for students just getting into photography? Or students who are looking to get a masters?

For students just getting into photography: don’t be afraid to do weird stuff. Don’t worry too much about film stocks at first, just take pictures and be open to feedback. Just because something is popular doesn’t mean it’s great. Looking more deeply into artists that I was really interested in was so important to me feeling confident enough to go crazy. For me, that was Catherine Opie, Robert Mapplethorpe, Christian Boltanski, Binh Danh, and Claude Cahun.

For students looking to get a masters: Doing deep research into programs that have specific interest to you, maybe through their programs, environment, or specific faculty. For me, a very important aspect of the research was facilities and funding that I was being offered, and whether teaching assistantships were required. So if you’re not interested in teaching, that’s something to consider. Some programs offer research assistantships too. And a big help and what made me feel confident in my decision of UNM’s program was that the current students and faculty were extremely down to talk to me on the phone, sometimes for over an hour, about their experiences there. And getting my own darkroom and studio was important to me too.

Do you have any up and coming works that you want to tell us about?

Right now I have one of my new pieces (cyanotype on pastrami) in a traveling exhibition through SPE. The exhibition is called New Wave and it will be at New Mexico State University, Anderson Ranch Arts Center, and Solano Community College.