Nonograms are simple and fun because they have the added bonus of producing a picture! They were first invented in the 1980’s in Japan, published under the name “Window Art Puzzles.” From there they migrated to the UK in the 1990’s, where they were renamed “nonograms,” and Games magazine began publishing them in the US under the name “paint by numbers,” which is how I first discovered them. Perhaps these puzzles are most famous for the various Nintendo spinoff games for the GameBoy and DS, namely Mario Picross and Pokemon Picross (picross being short for “picture crossword”).

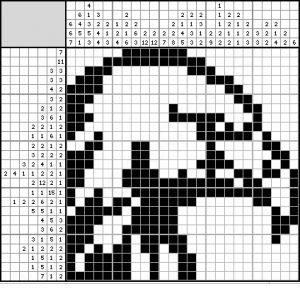

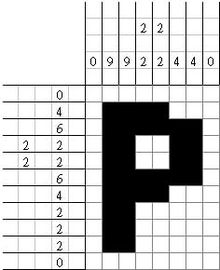

Like all the other puzzles discussed in this blog, the rules for nonograms are simple. The picture is supposed to be drawn in a grid of no specific dimensions (though usually at least 10×10). Along the sides of the grid there are a bunch of numbers, indicating how many squares should be filled in consecutively in that row or column; column numbers are listed along the top of the grid, row numbers are listed on the left. That is, a 4 along row 2 in Figure 2 means that the picture has exactly four boxes shaded in in that row, consecutively. The (2 2) in row 4 means that the picture has two boxes shaded, then at least one space, then another two boxes shaded. The goal is to create a picture which matches the numbers on the sides of the puzzle. While this sounds easy, it can actually become very challenging, very fast, and require quite a bit of guesswork depending on the difficulty level of the puzzle. Here are a few tips to help you get started!

One easy trick to look for rows or columns with a number that is more than half the length of the grid. For instance, in Figure 2 there are 11 column boxes. Looking at the second column, we can see that we need to fit nine boxes in a row. No matter how we orient those boxes, there will be a certain region that must be covered: namely, from row 3 to row 9. Thus we can shade those 7 boxes in, without exactly knowing where the other two will land.

Once we know that, we can use another technique which involves looking at numbers that are close to the edges of the grid. Consider, for example, the 4 in row 7. We know that the second column square in that row is shaded in, so that limits our possibilities for which boxes can be shaded in that row. In fact, there’s only one square available to the left of the second column, so we know there’s only two orientations for that block of squares: either its right up against the edge, or it starts in the second column. Either way, the third column and fourth column would both have to be shaded.

Nonograms are a lot of fun and I encourage you all to try them! There is a link below to online nonogram puzzles. Happy puzzling!

http://www.nonograms.org/nonograms/size/small

_________________________________________________

Sources:

http://www.conceptispuzzles.com/index.aspx?uri=puzzle/pic-a-pix/history

My roommate’s best friend Bryce doesn’t appreciate nonograms. People are always asking him, “Bryce, why don’t you like nonograms?” and he says, “If they can’t all be pictures of clowns, then what’s the point?”