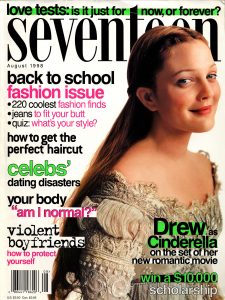

Ever After: A Cinderella Story (1998) starring Drew Barrymore and the indomitable Anjelica Huston has always been and always will be my most beloved example of cinema and it never really was for the story.

Everyone knows Cinderella, most cultures have their own version of it, so there was nothing to be overly impressed with there. What caught my attention the first time I watched it (which must have been ten years ago now) was the costumes. From being raised in a community children’s theatre, I loved to play dress up, and in this film everyone was dressed up like princes and princesses. As I grew older, I began to appreciate the costumes more and more. Take the gown Barrymore’s character Danielle (our Cinderella) wears to the ball:

The silhouette is striking to say the least. The transparency of the wings makes it seem like they omit their own light. She is glowing. She’s an angel. Let’s take a closer look.

The embroidery is so detailed, even though in the film we don’t get to see the dress up close like this at all. I was (and still am) entranced by the amount of work the costume department put into this costume, knowing that probably few other than themselves would truly appreciate it for the masterpiece it is. This level of dedication to detail was present in all the costumes.

Take this gown worn by Huston’s character Rodmilla (our wicked stepmother):

Green velvet with gold embroidery? I’m drooling. And the gathering at the waist and shoulders creates a plentiful layered look with lots of movement. This gown screams, “RICH AF.”

Of course, since the story is Cinderella, costumes have to take center stage. In the Grimm’s story, Cinderella can only go to the ball if her step-family doesn’t recognize her so her Fairy Godmother casts a spell on them that will last until midnight, which protects Cinderella. In Ever After, Danielle has no protection from that recognition. In a sense, she is actually her own Godmother in this respect. She has to quickly switch between the look of a French comtesse worthy of speaking to a prince and a peasant who works her family’s land.

Comtesse:

Peasant:

The costumes also gives us insight to Danielle’s relation to her step-family. Take the step-family’s casual wear:

This scene takes place first thing in the morning. These are their house clothes, they’re not even trying, and Rodmilla STILL has on a heavy patterned velvet cape and both sisters are wearing embroidered brocades. Whereas Danielle’s casual dress isn’t nearly as heavy or clean:

The material for her skirt looks like a rough canvas, her brocade looks so worn that it no longer has a form, and her blouse is so flimsy you could probably see right through it if you held it up to the light. This illustrates that the step-family can clearly provide Danielle with nicer clothes, but they don’t, heightening her alienation from them and our dislike for them as audience members who are led to take Danielle’s side.

Another instance of costuming lending aid to division is demonstrating the deep socio-economic divides among the classes, which Danielle teaches the narrow-minded prince is A) real and B) unfair. A perfect example is when Danielle is out with the Prince playing her role of comtesse and they get into skirmish with the gypsies in the woods. You can clearly tell who is who:

Even Danielle’s ratty peasant clothes look better than what the gypsies have on. Also, could the filmmakers make it any more explicit that we’re not supposed to trust the gypsies? Look at this picture, they’re all in these dark muddy colors: rust, navy, olive, burgundy, and straight up black. Danielle is looking ethereal in starch white. Great subtlety there, you guys. It nearly got by me. But as overplayed as this was, it exemplified the gap (more like canyon) between the ruling and the ruled.

The movie was mostly filmed on location in France, thoroughly transporting the audience to the time of noble-owned peasant-run farms and towering castles. One castle featured was Château de Hautefort:

Here’s Château de Fenelon:

And Château de Losse:

Paired with our costumes, the actors looked completely natural in these exotic locations. See how the fashion that our romantic minds assume people wear in these types of places are perfectly displayed in the film:

Fairytale costumes for a fairytale setting. I think the greatest example of visual blend is the ball scene when we see the royal family on their thrown:

We believe that they are royalty. This image alone without any context would convince anyone that they have lots of wealth and rule a large amount of people, in this case France. The tapestry behinds them not only shares the gold embroidery and jewels of their costumes, but the over all look substantiality.

Upon the film’s release in 1998, it was hailed in the media as the feminist Cinderella, a modern telling of the fairytale while still being set in the 16 century. Barrymore commented on this in an interview around the time of the film’s release. When asked by the host ‘What was wrong with the Cinderella that I grew up reading? Why didn’t you like it? What did you want to change?’ she replied, “There’s some values that don’t apply today, as far as like a woman who waits to be rescued and sort of dreams and hopes for things. I always thought that wishing was sort of odd when I was younger. I thought, God, you know if you really want something, go out there and make it happen.”

Ever After certainly portrays Danielle as a go getter. The film begins with her disguising herself as a comtesse to go buy back a man who works the estate with her, in essence risking her life. If Rodmilla (who sold the man in the first place to pay off a debt from her shopping addiction) ever found out, Danielle would be sold to another noble. If anyone in the royal or noble court found out that she was not of noble blood and in reality was just a commoner in a nice dress, she could be imprisoned, sold, shipped to the Americas, or killed. You can’t say she’s not brave. And beyond this, she’s willing to keep up this disguise just to keep seeing the Prince, with all the same possible outcomes if she’s discovered.

Aside from doing things labeled heroically brave, she’s brave in every day things as well. When she and some of her fellow workers go to sell their produce at the market, Monsieur Pierre le Pieu (played by Richard O’Brien of The Rocky Horror Picture Show) reveals to us that he’s been eyeing her for some time in this greasy exchange:

le Pieu: “Danielle De Barbarac, you get prettier every week.”

Danielle: “You, monsieur, are wasting your flattery.”

le Pieu: “I may be twice your age child, but I’m well endowed as evidenced by my estate. I’ve always have a soft spot for the less fortunate. You need a wealthy benefactor and I need a young lady with spirit.”

When he is spurned again, he bids farewell with, “I’ll buy nothing this week, and you’ll do well to remember that without my generosity your pathetic little farm would cease to exist. I’d be very, very careful if I were you.”

In the face of pure sleaze, she’s able to hold her ground and able to hold her tongue. If she were to really let him have it, she’d be whipped by Rodmilla, so we see that she’s smart and knows the consequences of her actions. She’s brave, but not stupid.

She even saves the Prince’s life, which he thanks her for (brownie points), when they’re caught by the gypsies in the woods. At the moment, she had been climbing a tree to get a better of view (they were lost and she insisted she climb instead of the prince since she wouldn’t want him to “break his royal neck”) and had taken off her dress for better mobility.

A crash course in Medieval fashion: the most decadent layers are on top to be seen, underneath is the brocade to give women the right torso shape for the dress to hang on, then are the undergarments like bloomers.

She climbs down while the Prince and the gypsies duke it out with swords despite the Prince’s order to “stay aloft.” She gets right in the fray, too, but doesn’t have the chance to really get to use the sword she grabs before she is restrained by the gypsies. The Prince tells them to let her go and they oblige. At this moment, everyone except Danielle is thinking that the gypsies are gonna either rob them both and leave them or rob them both and kill at least one of them. Danielle chooses neither and grandly says:

“I insist you return my things at once, and since you deprive me of my escort, I demand a horse as well.”

What a badass. Two seconds ago they were holding her with a blade at her throat and now she’s telling them to give her one of their horses. Then the gypsy leader gets tricky and says she can take whatever she can carry. So what does she do?

Just picks up the Prince and fucking leaves.

The gypsies are so taken back and amused that they give her the dress back and a give her a horse, as well as invite both of them to have dinner with them around a big campfire as they sing and drink and have a good time. Here’s your strong independent woman, for ya.

Of course, her attending the ball that the Prince has invited her to was a huge act of bravery. Up until that point, she’s let very few people see her all dolled up as a comtesse and now she’s going to go to a ball in front of hundreds of people when she’s still just a peasant in someone else’s clothes? Talk about guts. If there wasn’t danger these past few weeks of this disguise, there’s danger now. If she gets exposed, she’s dead. Unfortunately, that’s just what happens. Rodmilla sees her arrive and stand beautifully atop the stairs with her big fairy wings… and decides that this is not happening and actually rips a part of her wing off and tells everyone that she’s her slave.

*gasp*

*shock*

The shit has hit the fan.

Danielle has been so brave all this time thinking that this might actually work out and she could marry this man who’s she’s fallen in love with. She was even going to tell him that she was really a peasant that very night and she totally thought that he would still love her. But the truth comes out, not in the best way thanks to Rodmilla, and the Prince just loses it and calls her a liar and leaves.

But! The next day, Danielle is back up and working on the farm. What a woman. She loses her dream and claps back with, “I have work to do.”

Naturally, at this point Rodmilla is humiliated by the whole scandal and sells Danielle to none other than Pierre Le Pieu, who intends to break her like you would a wild stallion. Meanwhile, the Prince comes to his senses (believing her to be his one true love despite the fact that she’s a commoner who did sort of lie to him) and plans to rescue her.

Do you see this guy? Smelling her hair. Danielle’s not having it. So she rescues herself. While wearing shackles, she actually manages to corner him with two of his own swords and demand her freedom. It works. What a problem solver.

The Prince gets there too late, the dirty work is done. In fact, in the scene, he’s only just got off his horse when Danielle walks out of le Pieu’s castle all by herself.

Then the movie pretty much comes to a close with the Prince asking her to forgive him and love prevailing. Happily feminist ever after.

So sweet.

Danielle is the definition of a go-getter. The film is entirely based on her actions. She chooses to infiltrate the noble court to save her fellow worker’s life, she chooses to see the Prince again, she chooses to save his life, to go to the ball, to fight for her freedom, and ultimately she chooses to accept his offer of marriage. I personally think she’s a wonderful female role model and that this is a very feminist film.

But some people argue that this move, much like Danielle, is only pretending. This movie is only disguised as a feminist film. That while, sure, Danielle does a few brave things, it still portrays women in a bad light and enforces the idea that marrying rich is the answer to everything (something only a man can give you).

Opinion articles from this point of view often cite Rodmilla as being a perpetrator of the stereotype that women cannot be trusted with money. Rodmilla’s story is that she marries Danielle’s father, who has a thriving farm and big house and a good sized back account, but then once he dies rather quickly after their union, she squanders it all away. The money mostly goes to the marriage campaign of one of the step-sisters to the Prince. In fact, they eventually run out of whatever savings Danielle’s father had built up and go into debt, constantly having to sell Pierre le Pieu things like their tapestries and paintings and candleholders in order to keep buying new dresses and jewelry to trick the royal family into thinking they are much richer than they actually are.

So here we have a very independent woman as the head of the household, which is awesome, but then she’s written to be horribly irresponsible in the finance department. But did the screenwriters make this choice because Rodmilla was a woman? Does this mean that the filmmakers think that single women can’t handle wealth and high status? They need a man to manage property and finance so they don’t spend it all on clothes? No, I don’t think so. It’s not like they showed that all single French women with any capital to their name were terrible at keeping it. Besides, if for whatever reason they had decided to gender-swap Rodmilla and instead of a wicked stepmother have a wicked stepfather, the choice would have shown the exact same irresponsibility and vanity. It’s not as if men can spend all their money and even spend money they don’t have and somehow look better than if a woman did it. It’s just as unacceptable. It’s not like men can get away with it and women can’t.

In fact, this subplot of the household’s financial struggle doesn’t have to be there at all. In the Grimm’s story, it’s never stated that the family loses all their money somehow or that the stepmother is a shopaholic (actually in the Grimm’s story Cinderella’s father doesn’t even die, he just let’s his own daughter be abused by the stepfamily). I think having this new subplot just makes the film more interesting. It’s kind of fascinating to think of how people managed debt in the pre-industrialized era and watch the monetary struggle of farm-workers. It also raises the stakes for Danielle and makes the marriage to a wealthy prince all the more satisfying to the audience because now we are certain that her beloved farm is saved.

But that begs the question, does the household’s near-poverty status enforce the idea that marrying rich is the happily ever after? Well, you have to remember, this is the 1500’s. Women couldn’t outright own property unless their husbands died. And if a man had only a daughter and no son to truly inherit the land, the daughter’s husband gets the land.

Besides Rodmilla, there’s a handful of people who have a problem with the portrayal of the Queen. The Queen has the most power of any woman in the land, but in her scenes you could argue that she’s incredibly submissive to her husband and son. Then again, you have to consider the times. She even has the line, “Divorce is only something they do in England.” So yeah, she doesn’t always fight with full force when she argues with the men in her family, but women were also considered their husband’s property after marriage. I think that because she knew she had to stay in the relationship as a royal and social and religious duty, she didn’t pipe up too much because she didn’t want to cause more drama. Why make something so permanent more uncomfortable?

The film does pass the Bechdel Test. There are more than two female characters. They do talk to each other. Other than about a man (but not very often, to be honest). So it’s on the edge, but it’s passing.

I think the Prince is a good male role model, as well, despite the fact he is more of an object to be won as opposed to Danielle since as an audience we’re all rooting for her to marry the Prince at the end of the day. He starts off always scoffing Danielle’s non-feudal society ideals. He’s never had to question how society works because the society benefits him and his family, where all the power sits. Power wants to keep power, so of course his parents wouldn’t have given him any exposure to ideas that could lower their status such as equal opportunity and just penalty systems. But slowly over the course of the film, he take Danielle’s insights to heart. He announces to his parents that he wants to build a new university that would be open to all people “no matter their station” and he even invites the gypsies to the ball. We see a man in power be humbled and change his ways. He’s grateful to Danielle for this revelation. He actually listens to her and shares his feelings (not just the romantic ones) with her. The Prince becomes emotionally vulnerable, which I think is healthy for boys and girls to be exposed to. And yet, after all of these things that he’s learned from Danielle, he retaliates at the ball when he learns that she herself is a commoner, telling us that his acceptance did not go above his possibly subconscious thirst for power. Danielle’s common status is a threat to his position. A royal cannot marry a commoner unless that royal wants to be thrown out of their own court. It’s just not how things worked and no one had ever done it before. If the Prince had truly believed that blood shouldn’t matter, then he wouldn’t have retaliated at all. He eventually does come around, but it definitely takes some time. And to be fair, some of that retaliation is out of anger that Danielle had been lying to him about her identity, but he does reinstate that he “is a prince of France” and she “is just like them” (them referring to the lower-than-him stepfamily who is greedily clambering for a place in the royal court via marrying him).

So how do we reconcile the reality of the time period with feminist ideals?

Well, I think we should do just what Ever After does, which is make women realistic heroes for the time period. Danielle is as brave as she can be without getting herself outright beheaded. You know how the French love their guillotine.

Barrymore hailed the film as “contemporarily attainable” which I think is true. It’s still a romantic version of Cinderella. Being rescued is romantic, marrying rich is always a plus, but I think the character of Danielle is meant to show us through her actions and progressive views that wealth and being saved by someone else is not everything. Danielle’s life was already fulfilling, now she’s just married to the love of her life who happens to be a prince.

I was whisked away with this film, always have been. It’s visually stunning and endlessly empowering. The castles add permanence to the romanticism of France and the costumes speak of the divide between nobles, royalty, peasants, and gypsies down to the very last bead and button, and it portrays Cinderella as a person who loves love, but who can also make decisions of her own without being naïve.

And besides, I’m a sucker for a good Cinderella story.

-

Ever After. Dir. Andy Tennant. By Andy Tennant, Susannah Grant, and Rick Parks. Perf. Drew Barrymore, Anjelica Huston, and Dougray Scott. Twentieth Century Fox, 1998. DVD. "Ever After." Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, 14 Jan. 2017. Web. 18 Jan. 2017. Barsam, Richard Meran, and Dave Monahan. Looking at Movies: An Introduction to Film. New York: W.W. Norton, 2016. Print.