Carol is a 2015 film directed by Todd Haynes, with a screenplay written by Phyllis Nagy. It is based on the 1952 romance novel, The Price of Salt, by Patricia Highsmith (The Talented Mr. Ripley, Strangers on a Train). Carol tells the story of two women in early 1950s-New York who begin a secret sexual and romantic affair with each other, and the consequences that follow. Meek and soft-spoken Therese (Rooney Mara) is working retail at a department store when she meets the older and more glamorous Carol (Cate Blanchett), who is looking to buy a Christmas present for her young daughter. The two strike up a friendship, causing Carol’s soon-to-be-ex-husband to become suspicious of the nature of their relationship, as Carol had had an affair with another female friend in the past. Carol takes Therese on a road trip, where they kiss and have sex together. After discovering that a private investigator had been hired to collect evidence towards the sexual nature of their relationship, Carol abandons Therese to return home to New York and the relationship between the two becomes strained. The film was nominated for six Academy Awards and nine British Academy Film Awards.

The Price of Salt caused quite a stir when it was first published. Highsmith published it under a pseudonym, Claire Morgan, as she knew that reception likely wouldn’t be entirely positive, and because she didn’t want to be labeled as “a lesbian-book writer”. However, the novel was received quite well in the lesbian community, most notably because of the happy ending that most queer novels did not have at the time. Neither of the women dies, neither retreat back to an unhappy relationship with a man, neither end up sad and alone. This was rare for queer characters, lesbians especially. Even today the media has a problem with the “bury your gays” trope. GLAAD’s “Where We are On TV” report for the ’16-’17 season found that of 895 regular characters on broadcast networks, 43 identified as LGBTQ. 28 of which were queer women. Of those 28, 12 were killed by the end of the season. This makes 2016 a very deadly year for queer women on broadcast television.

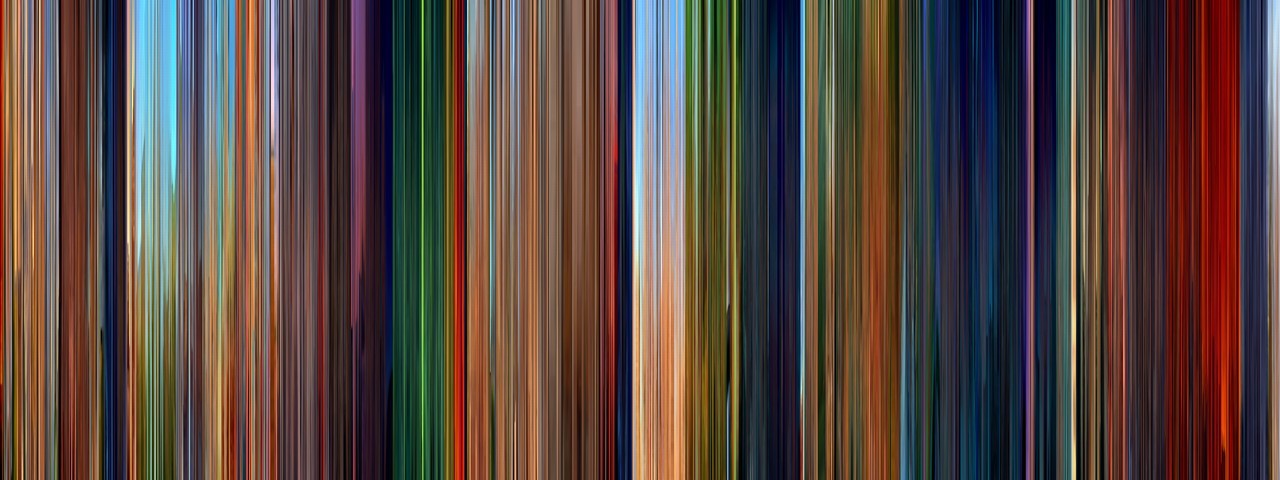

The happy ending, although somewhat ambiguous, was one of the many reasons I enjoyed Carol. I thought the costumes were beautiful, and the use of Super 16mm film gave it a wonderful vintage haze. Cate Blanchett’s performance as Carol had me far more emotionally invested than I expected to be, going in; although at times it felt to me that Rooney Mara wasn’t doing much beyond reciting her lines. However, this could be due to the quiet nature of Therese — who spends most of the film allowing things to happen to her, without pursuing her own goals at all. Which makes the ending, (spoilers!) when Therese seeks out Carol all on her own after initially rejecting her, all the more meaningful. Still, I would have liked to see more emotion from Mara.

In 2016, the British Film Institute named Carol the best LGBT film of all time. This I can’t agree with. The film was good, yes, but to be named the best LGBT film of all time, I’d expect to see more about the society they are living in and what kinds of bigotry they are dealing with. As it is, the people around them seemed somewhat… indifferent to the existence of LGBT people. Carol’s husband knows that she had a previous relationship with a woman, but doesn’t seem bothered beyond the usual jealousy. Therese’s boyfriend can’t imagine two boys falling in love with each other, but his thoughts about it aren’t strong at all. He isn’t all that concerned when Therese exhibits deep, romantic feelings for Carol except, again, for the expected jealousy. This doesn’t feel right for a time period that produced Boys Beware and called queer folks “criminals” and “sick in the mind”. Is it because Therese and Carol are women? I’m not intensely familiar with the homophobia of the 1950s, but from what I understand, much of it was directed toward gay men, and lesbians were often able to dodge it through the guise of close friendship. Not to mention that the definition of “sex” was something that required a penis — so how could two women even have sex? All things considered, I still think the film could have explored further into what the two women were really up against.

“50 Years of Theater of the Ridiculous” Martin E. Segal Theater Center, 2017.

Baur, Gabrielle, director. Venus Boyz. Clockwise Productions, 2002.

“THE HOMOSEXUALS.” CBS, 1967.

Jo Krals, Bobbi, director. Rebels on Pointe. Icarus Films, 2017.

Kaye, Helen. “Theater Review: ‘Milk Milk Lemonade’.” The Jerusalem Post, 26 Aug. 2014.

Kupcinet, Irv. JUDY GARLAND: A GAY ICON DEFENDS HER GAY AUDIENCE, A RARE INTERVIEW. 1967.

Roberts, John. “MilkMilkLemonade – Ovalhouse, London.” The Reviews Hub, 12 Oct. 2014.