RAM. Of what primordial light, And starry explosions begotten, Shaped from liquid rock and frothing blooms, -VAM- Catalytic thunder and watery hell, A spontaneous bog long forgotten? LAM. Whence did I come? See me: Sapiens! See how far I’ve grown and shrunk, free and domesticated. Life to the void with interest sold. OM. Atop smogged cliffs swaying, do I reach out too soon? HAM. Would you catch me in my blunder, oh shimmering bell, Intoxicated, so schizophrenic amid burning plumes? AH. Would you lend me clarity, a touch of your boon? See me: I want to love! YAM. Come sit as one, round a new seedling in Gan Adamah.

Some Background

Born in Los Angeles, California, in 1904, Isamu Noguchi was a world renowned Japanese-American sculptor. Two years after his birth, his family moved to Japan; his parents, Yone, a Japanese poet and an authority on art, and Leonie Noguchi, an American writer, separated shortly after. Isamu then lived with his mother, Leonie, while Yone remarried, and was eventually an attendee of a Japanese and Jesuit school. When he was 13, Noguchi moved back to the United States and studied at the Interlaken School, an all boys school, in Rolling Prairie, Indiana. At Interlaken, each student was prepared for university with practical training in a variety of fields. There were also daily practical assignments concerning woodwork, metal crafting, working with light or power plant technology, and farming methods. He took a sculpting class as an elective which likely pushed him to take on a job with sculptor Gutzon Borglum after high school. In New York, after high school, Noguchi decided to take art classes at the Leonardo Da Vinci Art School. His mother remained supportive through all of his artistic endeavors, as did his mentor at L.D.V.A.S. Onorio Ruotolo, a sculptor and poet from Italy who was inspired by social struggle, poverty and the horrors of war.

Noguchi’s artistic point of view, a combination of both Japanese and Western traditions, is thought to be highly influenced by the similarities between his upbringing both at home and in an educational setting throughout his life.

After winning a Guggenheim award at age 22, Isamu was given the opportunity to work as an assistant to Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncuși in Paris. Also known as the known as the patriarch of modernist sculpture, the artist emphasized geometry in his pieces and consistently used natural materials such as wood and marble, which is likely to have influenced Noguchi’s use of the same techniques and materials used in his own sculptures.

Once back in the U.S. Noguchi had limited success until an exhibition of 15 bronze heads put him on the map in 1929. He became even more widely known in the United States after his first sculpture, the Relief mural, was commissioned for the Associated Press building in Rockefeller Center in 1940. Isamu had two main studios that he used to work in; one in New York and one in Japan. His first studio came to fruition in 1942 when he was 38 years old.

Noguchi’s work is said to adhere to is surrealism and abstract expressionism. The artist finds overlap of the archaic (the natural resources and appearance of such used as the materials in all of his works), with the modern and postmodern style. He is also said to be an accomplished synthesizer of opposites. His sculptures and furniture are easily his most influential kind of work; largely created with the intention of integrating the consideration of how the public will interact with the designs and enhancing public spaces, as is the case with the Skyviewing Sculpture in Red Square on Western Washington University’s campus.

The Sculpture

The Skyviewing Sculpture, a dark brownish-gray half cube, is a balanced combination of straight and curved lines; it offers a circular view on all skyward sides, and is hollowed out from the bottom. Created by commision for Western, it references his appreciation for the universe and larger than life ideals which are exemplified by the combination of archaic and modern design principles. The meaning behind the piece, in alignment with the title, is to encourage the viewer to stand beneath it and view the sky and space with a new, wider perspective.

The sculpture was created in December of 1969, just 5 months after the moon landing. It would be far from a stretch to assume that the artist did not draw some inspiration from the mission, similarly to the Space Needle, which was designed to be used as a viewing tower 1962. Conceptually, the two pieces are similar in intention.

Furthermore, inspiration likely came from the 1968 release of the book and film, 2001: Space Odyssey, written by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke. The film touches upon creation by an ancient extraterrestrial civilization whose monoliths affect early hominids as an explanation to the rise of civilization. The film also deals with concepts such as technological innovation, space travel, life and death, reincarnation, and metaphysics in general. As the renaissance man that Isamu Noguchi was, it is only fitting for him to have designed a piece that was meant to connect the viewer to a meaning that was not only up for interpretation, but imposing on their preconstructed impression of their own existence.

Existentialism was likely influential in shaping the theme of Skyviewing Sculpture. Questions such as, but not limited to; where do we come from? What is human life and civilization in the grand scheme of things? What is the crossing point between nature and man, or the crossing of nature and extraterrestrial civilizations? Is man a crossing point?

Our Work

We seek to expand on Noguchi’s work. The Skyviewing Sculpture is a hybrid piece conceptually for both mass and dissolution. Anchored, yet willing to rise up, as if it represents a nexus between the planet and the heavens. Humanity is caught in-between, like the sculpture itself. Perhaps some crossings have already occurred, but are just occulted, like a feeble drip through a crack, through the dam soon to burst.

We seek to expand on Noguchi’s work. The Skyviewing Sculpture is a hybrid piece conceptually for both mass and dissolution. Anchored, yet willing to rise up, as if it represents a nexus between the planet and the heavens. Humanity is caught in-between, like the sculpture itself. Perhaps some crossings have already occurred, but are just occulted, like a feeble drip through a crack, through the dam soon to burst.

Credits

Music in the video by Dexter Britain

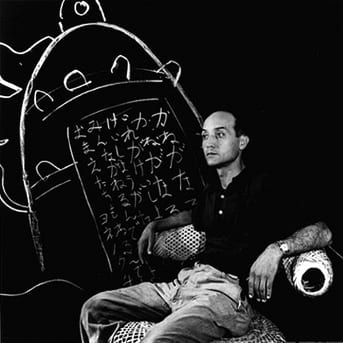

Photo of Isamu Noguchi is public domain

Photo of Relief Mural is by josullivan.59 on Flickr

All other media was created by the group.

The rendering was created by Cole Behrndt with creative input from Claire Ott and Giovanni Roverso. Research was spread between group members, the blog post was primarily authored by Claire Ott and Giovanni Roverso.

Bibliography for research

“Biography.” Biography | The Noguchi Museum, www.noguchi.org/noguchi/biography.

Brenson, Michael. “Isamu Noguchi, the Sculptor, Dies at 84.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 31 Dec. 1988, www.nytimes.com/1988/12/31/obituaries/isamu-noguchi-the-sculptor-dies-at-84.html?sq=Isamu+Noguchi&scp=7 .

Jones, Jack. “Renowned Artist Born in L.A. : Sculptor Isamu Noguchi at Age 84.” The LA Times, The LA Times, December 31, 1988, http://articles.latimes.com/1988-12-31/news/mn-650_1_isamu-noguchi

C, Kevin, et al. “Noguchi® Table Reviews Summary.” Herman Miller, 29 July 2018, store.hermanmiller.com/living/coffee-tables-and-side-tables/noguchi-table/103695.html?lang=en_US&mrkgcl=583&mrkgadid=3200073502&adpos=1o1&creative=177757911247&device=c&matchtype=&network=g&gclid=Cj0KCQjw6fvdBRCbARIsABGZ-vQesrUjoMFde-aEZcPNlgK9JxfJWtV3RwB68lbQMWyMsPlKR-sptRkaAq9pEALw_wcB

Hart, Dakin. Isamu Noguchi. Archaic/Modern. D Giles Limited, 2017.

“Isamu Noguchi Overview and Analysis.” The Art Story, www.theartstory.org/artist-noguchi-isamu.htm.

Metmuseum.org, www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/2000.600.14/.

“News.” News | Art Exhibits of NYC | Rockefeller Center, www.rockefellercenter.com/art-and-history/art/news/.

The Noguchi Museum, www.noguchi.org/museum/collection/projects.

Period Paper. “1917 Ad Interlaken Headmaster Rolling Prairie School – ORIGINAL ADVERTISING TIN2.” Period Paper, www.periodpaper.com/products/1917-ad-interlaken-headmaster-rolling-prairie-school-original-advertising-074187-tin2-184.

“Western Front – 1969 December 9.” Western Front Historical Collection, content.wwu.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/wfront/id/36217/rec/6

Herrera, Hayden (21 April 2015). Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 68–71.

“The Art of Freedom: Onorio Ruotolo and the Leonardo da Vinci School”. https://www.academia.edu/1460390/The_Art_of_Freedom_Onorio_Ruotolo_and_the_Leonardo_da_Vinci_School .

Getty Record. Constantin Brancusi, French, born Romania. 1876–1957 https://www.moma.org/artists/738 .

Blog post about “Pylon.” http://detroit1701.org/Pylon.htm .

Kubrick, Stanley. 2001: Space Odyssey. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1968.

Leave a Reply