May 11th, 2022. Well this is it! After spending 50 days on the ocean, no trees in sight and limited connection to our outside lives, we are back on land. Our expedition to study the distribution patterns of hydrothermal snails in relation to their symbionts was a roaring success. We collected a ton of data and samples to be processed back home, made new discoveries and generated new questions, and had the experience of a lifetime. The ability to study such unique sites and habitats, especially right after a huge volcanic eruption has been an immense privilege. This would not have been possible without the hard work of everyone involved, especially for the planning that went into this cruise. We also are so grateful to the Kingdom of Tonga for allowing us to research their waters, and we are sharing our data and findings with them as we delve in deeper. I just want to say –

Thank you to the AMAZING science party on the TGT

This would not have been possible, or as enjoyable, if the team of scientists on board were not so incredible. The science party mixed with the teams from Jason and Sentry, and the crew members of the TGT made for a welcoming, enthusiastic, and fun group. We all got along so well, and facilitated a hard-working environment that supported each other as a solid team. Even on bad days, which inevitably happens after spending so much time isolated with the same people (and no alone time), we gave each other space and forgiveness.

During our final transit back from our last site, Mata Tolu, we were able to reflect on the cruise as a whole and were impressed by numbers! This 50-day cruise boasted 35 million liters of water filtered from the McLane pump and Sentry’s SyPRID. Within that water we were able to identify over 2,000 larvae that belonged to 72 distinct morphotypes (similar form). While alternating Sentry and Jason dives at our 7 separate sites, each vehicle spent over 200 hours in the water! Jason allowed us to sample over 1,000 snails and opportunistically collect 51 lbs of ash from the recent volcanic eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano. During this time at sea we ended up traveling nearly 7,000 miles across the ocean, which is enough to earn each sailor a sparrow tattoo. During this long time we had many celebrations though, for holidays, birthdays, and even the captain’s promotion!

On the final days of this transit we finally had to organize and pack everything that we can brought out and collected over the past two months. We had samples in every fridge and freezer, at different temperatures and preservation types. We had to plan how we were going to get all of them back, shipping in acceptable quantities, scheduling pick-ups and dry-ice shippers. All our lab gear lay strewn about the ship, where we realized we probably should have been labeling everything each lab brought. I swear as we were packing up we had a lot more things than we came with, but we ended up getting our freight container fully packed! It’s kind of like Tetris, only the shapes are even worse with lab instruments, and if you pack it wrong things will break! Thankfully afterwards we only had a couple extra coolers that could easily be checked with our luggage on the way back. Most of the stuff we brought is staying on the ship until the ship reaches Newport, Oregon around May 20th. This way we don’t have to ship all the way from Hawaii… However, we packed up everything nicely so the team that’s meeting the ship will not have more work than necessary. (We really appreciate the OIMB lab members heading down there).

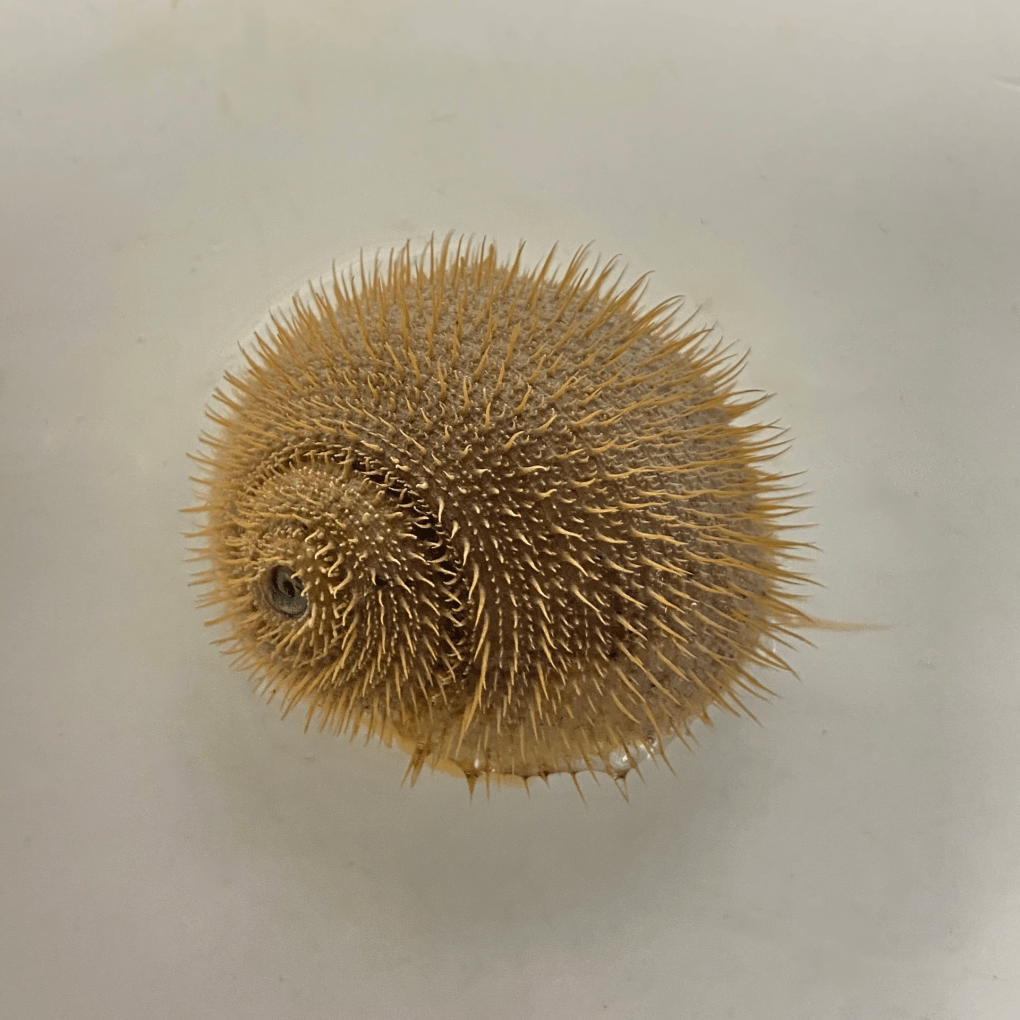

Alviniconcha boucheti

Our last creature showcase is of our third Alviniconcha species, Alviniconcha boucheti. Although not named after any other punk band members, it is named after Philippe Bouchet, a prominent deep-sea gastropod biologist. This snail has the most diversity in spine height, with an alternating pattern of long and short spines. This photo shows the varying lengths clearly. Fun fact is that these spines are not super hard, they actually feel closer to when you touch the hook end of VELCRO. Boucheti tend to dominate the more northern sites. We even found it at our West Mata site, Mata Tolu! All these snails host symbiotic bacteria that allow them to live at these hydrothermal vents. These bacteria are involved in chemosynthesis – using energy from chemical reactions to create food. Each snail species is typically associated with certain bacterial communities. When these snails acquire them, or why those communities, is another question we are hoping to answer with our results.

Thank you to those who followed along with us on this expedition, especially those that continually reached out to us at sea. Our friends and family kept us going when the times were tough, and we love to tell you all about what we’ve done and discovered! All that’s left to say is:

Snailed it!

If you enjoyed my blog and want to keep up with my future research or connect follow me on

Instagram: @djdavis123

Twitter: @dexterity_no