By Tanika Ladd

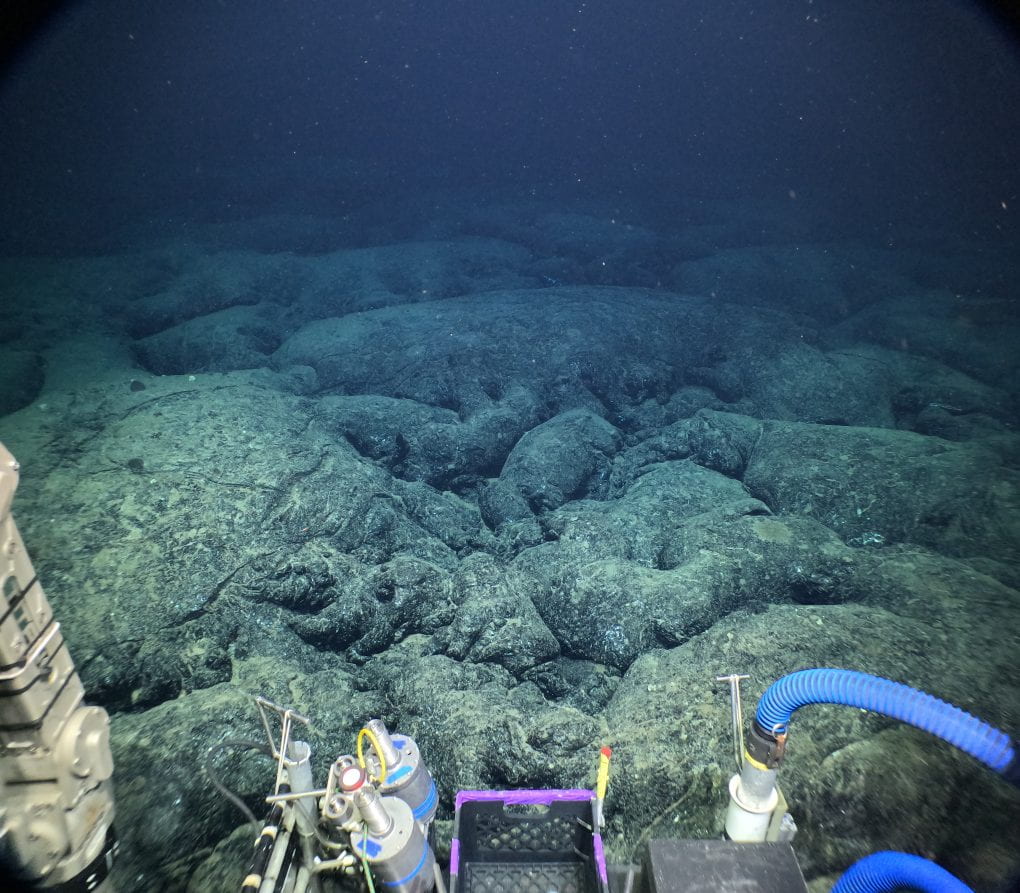

As this cruise and this project are coming to an end, I have been reflecting on what a journey it has been. Three years ago, I had almost no idea what it took to visit and study the deep sea. Now, at the end of almost 30 days at sea, it is routine to wake up and watch Alvin launch. When we are surrounded by all the scientists and Alvin pilots observing first-hand the thriving ecosystems living 2500 m below us, it is important to remind ourselves how extraordinary this all is. Diving in Alvin is one of the most amazing experiences of my life. Like my co-observer, Davide, said during our dive together – landing on the seafloor is an otherworldly experience. The rock features and the unique animal communities found down there in complete darkness are lit up just for us.

Images taken from Alvin during this cruise (AT50-20). Shawn Arellano, Chief Scientist, WWU; Alvin Operations Group; National Science Foundation; @Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

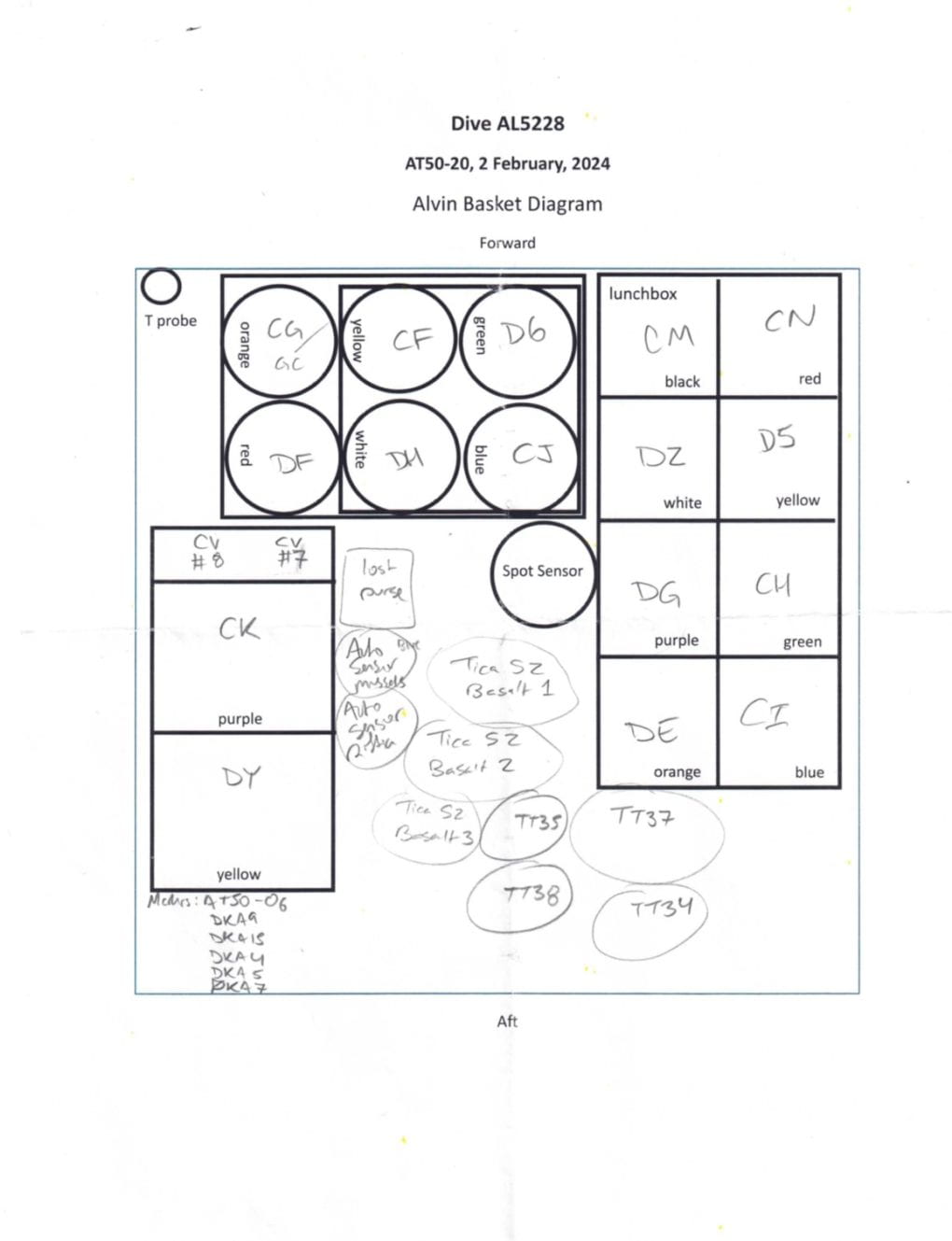

But we are not just tourists exploring these spectacular places – we have so much work to do during our precious time on the bottom of the ocean. For the science team, planning each dive has taken months of thought and prep. We need to make sure we have the correct tools and sampling boxes to do the work and enough space on the Alvin “basket” (the platform on the front of Alvin that carries all the science gear) for all the deployments and recoveries. In the images below, you can see the many different types of tubes and boxes that we fill with sampling and experimental devices, each with their own purpose, and that we ask the Alvin team to squish onto the basket for us. The “lunchbox” in the middle image is specifically designed for picking up colonization sandwiches and it has 8 separate inserts that allow us to keep them separated during recovery. In the days leading up to dives, the scientists work with the Alvin team to make sure our plan can be executed and that the weather will allow us to dive.

Images of science gear on the basket and a basket diagram that is sent with the divers to record sample collected. AT50-20 Shawn Arellano, Chief Scientist, WWU; Alvin Operations Group; National Science Foundation; @Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Photos by Tanika Ladd

Everything that happens during a dive is the responsibility of the 3 people in the sub (usually two scientists and one Alvin pilot), so we definitely do our homework the night before. The Alvin pilots are impressive (they go through some difficult training!) and they can use the Alvin manipulators (or arms) to do some careful and precise work, like picking up mussels or placing all our experimental deployments. For this project, we are asking a lot of the Alvin team and pilots because we have SO MANY things to deploy and recover. In the sub, while the pilot is driving and using the manipulators, the scientists are busy directing the science and taking video and notes of all the work. Doing an experiment at the bottom of the ocean where you need a large submersible with big metal arms to place a bunch of small colonization surfaces and tube traps in precise locations near some really hot hydrothermal fluids is no easy task.

Image of Alvin pilot Tony Tarantino, Tanika Ladd, and Davide Corso during their dive. AT50-20 Shawn Arellano, Chief Scientist, WWU; Alvin Operations Group; National Science Foundation; @Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Photo by Tony Tarantino

BUT we did it! Over the course of 3 cruises, we have deployed/recovered a total of 51 tube traps and 140 colonization “sandwiches”. The experiments may seem chaotic while they are happening, but we have gotten some really cool data from some of our first attempts at trying out these experiments! There are still so many samples we have to sift through (literally on a microscope sifting through tiny rocks and animal goo to pull out larvae), but all our hard work, with so much help from the captain and crew of the R/V Atlantis and the Alvin team, has made this cruise and the project a success. I can’t help but come home from an exhausting and non-stop 30-day cruise feeling exhilarated. I don’t think my words can fully describe how this ending feels but I just want to say that I love being a deep-sea researcher and I hope that I can keep exploring, learning, and spending my time surrounded by the ocean.

Image of the R/V Atlantis and Alvin during a dive recovery (left) and and image of a sunset (right). AT50-20 Shawn Arellano, Chief Scientist, WWU; Alvin Operations Group; National Science Foundation; @Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Photos by Tanika Ladd

Tanika Ladd is a postdoctoral researcher working at Shannon Point Marine Center (Western Washington University). Her time working with Shawn Arellano has converted her to the dark side (of the ocean, that is) after spending a lot of time thinking about the sunlit ocean. Her research interests include understanding interactions between microbes and animals and how energy and carbon flow through ecosystems, from primary producers to higher trophic levels.

EPR Biofilms4Larvae project is a multi-institutional NSF grant: OCE-1948580 (Arellano), OCE-1947735 (Mullineaux), OCE-1948623 (Vetriani).

Also find us on Instagram! @larvallab, #Biofilms4Larvae

The Inactive Sulfides project is a multi-institutional NSF grant: OCE-2152453 (Mullineaux & Beaulieu), OCE-2152422 (Sylvan & Achberger).

Also find us on Instagram! @jasonsylvan, #LifeAfterVents

I’m so happy for you and your research. It’s is great that all has gone as you hoped. Keep up the good work. I’m curious how long it takes to get down to the (floor) and back up. Happy travels Grandma Kim

Hi Grandma Kim! Thanks for reading! I wanted to answer your question about how long it takes to get to the seafloor and back up in Alvin. At these sites, the depth is about 2500 m and it takes us about 1.5 hours each way. The pilots can alter this time some by making the sub more or less buoyant in the water column but this was pretty typical timing for our dives. On the way up and down you can see bioluminescence (small organisms that produce light) out of the port holes but otherwise the sub lights are off and it is mostly dark so we take the time to prepare ourselves for the science on the way down and report back to the surface on the way up to give scientists on deck time to prepare for the samples coming up.