April 28th, 2022. It’s nearly the end of our long journey in the southwest Pacific. While we would be diving at Mariner, the southernmost site in the Eastern Lau Spreading Center, weather said otherwise. Instead, for our last site we are currently near West Mata, a volcano southwest of the Samoas. A 40-hour transit from Tu’i Malila. While this site is outside of our original sites, it hosts some of the snail species we’ve been studying. Since we are looking at the interactions between the geology, chemistry, and symbionts on adult snail distributions, we can compare with this additional location. Alviniconcha sp. also host unique groups of symbionts, so it will be interesting to compare the free-living symbionts communities between our sites and a new location.

For those unfamiliar with the term, a larva is the immature form of an organism before it metamorphoses into a physiologically different form. This means many larvae can look completely different from their adult forms. Think of a caterpillar turning into a butterfly. Caterpillars are larvae!

On this cruise we are particularly interested in finding the larvae of the Alviniconcha and Ifremeria sp. snails we are studying. This is not an easy thing to do. With the samples collected by Jason, Sentry’s SyPRID, and the McLane pump, our team of sorters pick through water, sediment, and snail bucket dregs searching for them. We work day and night. If any of our deployments come up at 2am, then we sort all morning. We plan accordingly though, taking naps, getting snacks, and playing music to keep us awake and focused. Here’s a photo of 9 different larval snails, gastropod veligers, we’ve found on this cruise that highlight the beauty and diversity of these organisms. The middle veliger has its “velum” out, a lobe covered in small hairs that it swims with. However, we are not confident on which species these veligers belong to. We’ve actually identified 23 different gastropod veligers so far! Unfortunately, we won’t be able to confirm their mysterious identities confidently until we do DNA sequencing on these individuals back on land.

Gastropod veligers are not the only larval type we’ve been finding on this cruise though. We pick out every larval type we find, separated by morphotype (form). Since they are so tiny, we are sorting these samples under dissecting microscopes where we have to fight the rocking and shaking of the ship’s movements to grab them. While some larval forms, like gastropod veligers, may look like their adult forms (or at least like a snail), here are some others that look different. The in the top-left of the left collage there is a larval crab and shrimp, also known as zoea. The top-right is a bivalve pediveliger (veligers are mollusc larvae) that will develop into a mussel. You can see its foot sticking out, one of the ways it moves around. The bottom left is a nectochaete, which will turn into a polychaete. From a golden-winged angel into a marine worm! In the right collage the top-left is another morphotype of nectochaete we’ve found. Even within a larval type the morphotypes can vary drastically. The top-right is a parenchymella, which will turn into a sponge. The bottom two pictures are the larval forms of a barnacle. They look completely different, right? The bottom-left is the nauplius stage, with distinct horns, and the bottom-right is the cyprid form. These amazing photos were taken on a compound microscope by Tessa Beaver (WWU) and Avery Calhoun (OIMB).

One particular larva we’ve been focusing on during this cruise is from one of our study snails, Ifremeria nautilei. The Warén’s larva. These “fat Y”-shaped larvae are uniquely brooded by female Ifremeria within a brood pouch in their foot. Little is known about these larvae, but we’ve been setting up live cultures throughout the cruise to research their developmental stages and temperature sensitivity. It’s been very exciting to map out the different stages we’re seeing, watching as a culture changes from one day to the next. We do not know at what stage these larvae are released from the adult, whether it’s as a veliger, or earlier in the Warén’s stage. Excitement within the science party occurred when we produced the first culture of larvae to develop the larval shell, documenting the transition into a veliger. Using a broken pair of polarized sunglasses found while snorkeling during our shelter in place, we were able to see the birefringence of the shell reflecting back at us under the scope. Why is this exciting? Because it also might be the first time someone has seen this development occur.

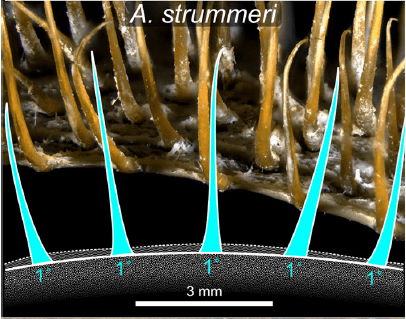

Alviniconcha strummeri

As the next part of our creature feature, I’d like to show you the second of our three Alviniconcha species, Alviniconcha strummeri. This punk rock snail is named after a member of the punk rock band, the Clash, Joe Strummer. Named by: Shannon Johnson (punkrocksnails on Instagram/Twitter) A fitting name for these snails that have adapted to live in one of the most extreme habitats on the planet. This species is easily identifiable by the spines on its shell. This species only has long spines of the same length, while the other species have varying lengths. A. strummeri dominates the more southern of our sites along with A. kojimai from the last post. One interesting aspect about Alviniconcha is that under their periostracum (the outer layer of the shell), their shell is gold! You can see at the apex of this individual a little bit of it sticking out. However, we are only collecting these snails for the scientific wealth they hold. Here’s an article about them if you want to learn more: https://www.npr.org/2014/12/20/372052995/a-snail-so-hardcore-its-named-after-a-punk-rocker