By Moira Stockton, Research Assistant

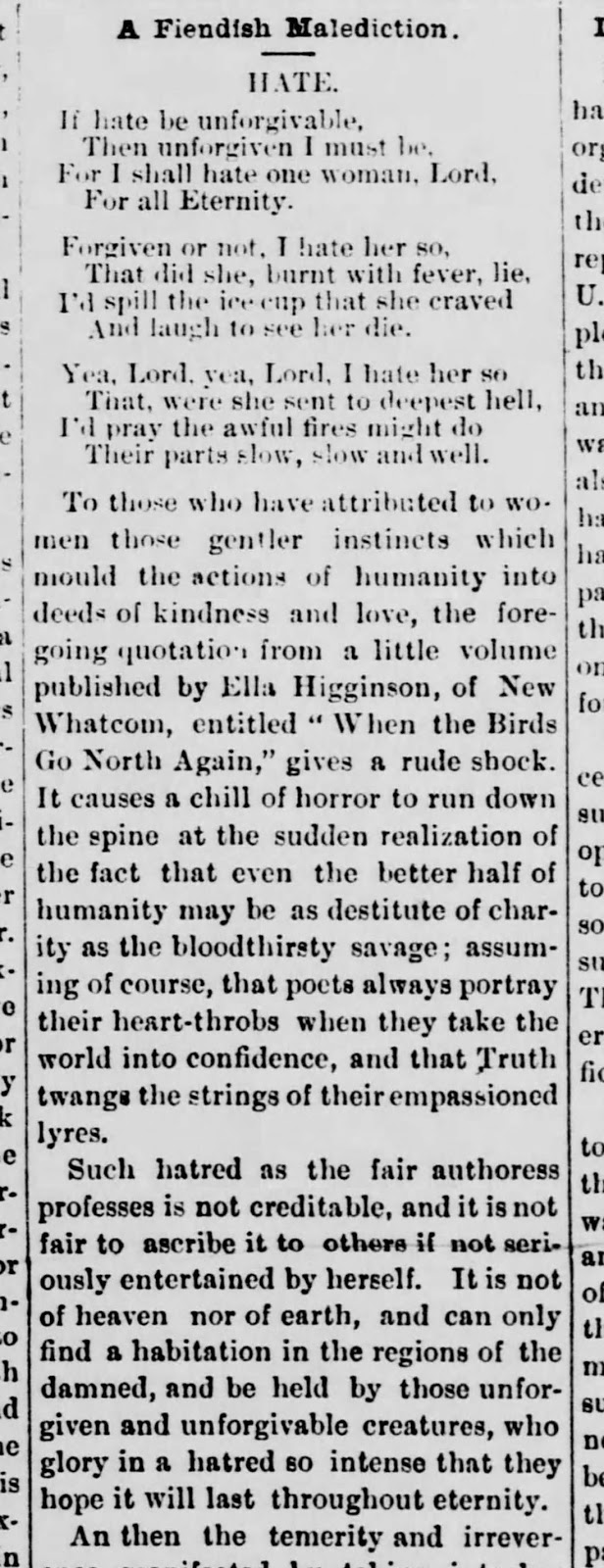

Dr. Laura Laffrado has located only one negative review of Ella Higginson’s work since she began the Ella Higginson Recovery Project. However, until recently, Dr. Laffrado was unsure what the review said, as the only reference to it was in a 1935 letter Higginson wrote to Alfred Powers (1887-1983, Oregon author and journalist). The review has now been located though the author of the review remains unknown. The review appeared in The Washington Standard (Olympia, Washington). The subject of the review was Higginson’s poem, “Hate,” which appears in Higginson’s book When the Birds Go North Again (1898). The review, titled “A Fiendish Malediction” and published August 24, 1900, reprints “Hate” and harshly critiques the poem and its author. Transcription below:

“Hate” as it appears in Higginson’s When the Birds Go North Again (1898).

To those who have attributed to women those gentler instincts which mould the actions of humanity into deeds of kindness and love, the foregoing quotation from a little volume

published by Ella Higginson, of New Whatcom, entitled “When the Birds Go North Again,” gives a rude shock. It causes a chill of horror to run down the spine at the sudden realization of the fact that even the better half of humanity may be as destitute of character as the bloodthirsty savage; assuming of course, that poets always portray their heart-throbs when they take the world into confidence, and that Truth twangs the strings of their empassioned lyres. Such hatred as the fair authoress professes is not creditable, and it is not fair to ascribe it to others if not seriously entertained by herself. It is not of heaven nor of earth, and can only find a habitation in the regions of the damned, and be held by those unforgiven and unforgivable creatures, who glory in a hatred so intense that they hope it will last throughout eternity.

published by Ella Higginson, of New Whatcom, entitled “When the Birds Go North Again,” gives a rude shock. It causes a chill of horror to run down the spine at the sudden realization of the fact that even the better half of humanity may be as destitute of character as the bloodthirsty savage; assuming of course, that poets always portray their heart-throbs when they take the world into confidence, and that Truth twangs the strings of their empassioned lyres. Such hatred as the fair authoress professes is not creditable, and it is not fair to ascribe it to others if not seriously entertained by herself. It is not of heaven nor of earth, and can only find a habitation in the regions of the damned, and be held by those unforgiven and unforgivable creatures, who glory in a hatred so intense that they hope it will last throughout eternity.

An [sic] then temerity and irreverence manifested by taking into her defiant confidence One of all others whose nature beams with forgiveness and love; one who came on earth and died to inculcate the doctrine of love, forgiveness and fraternity, peace on earth and goodwill among men. She prays—not in His name surely—that a fellow being, on her own judgement, may be sent to the “deepest

hell,” and that the awful fires may “slowly do their part,” so as to inflict the most exquisite, lasting and horrible torments. This seems so hellish (the proper word, dear reader,) it challenges belief that a human being could have deliberately given expression to such cruel sentiment.

hell,” and that the awful fires may “slowly do their part,” so as to inflict the most exquisite, lasting and horrible torments. This seems so hellish (the proper word, dear reader,) it challenges belief that a human being could have deliberately given expression to such cruel sentiment.

It is safe to say that if good old St. Peter ever catches a glimpse of that little poem, Ella will never enter the pearly gates. She will be compelled to finish out such profound hating “to all eternity,” at New Whatcom, or in Hades, for nobody with such a lump in her throat will be allowed to enter the

kingdom of heaven.

kingdom of heaven.

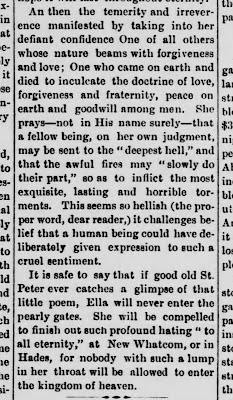

The review as it appears in The Washington Standard (August 24, 1900.)

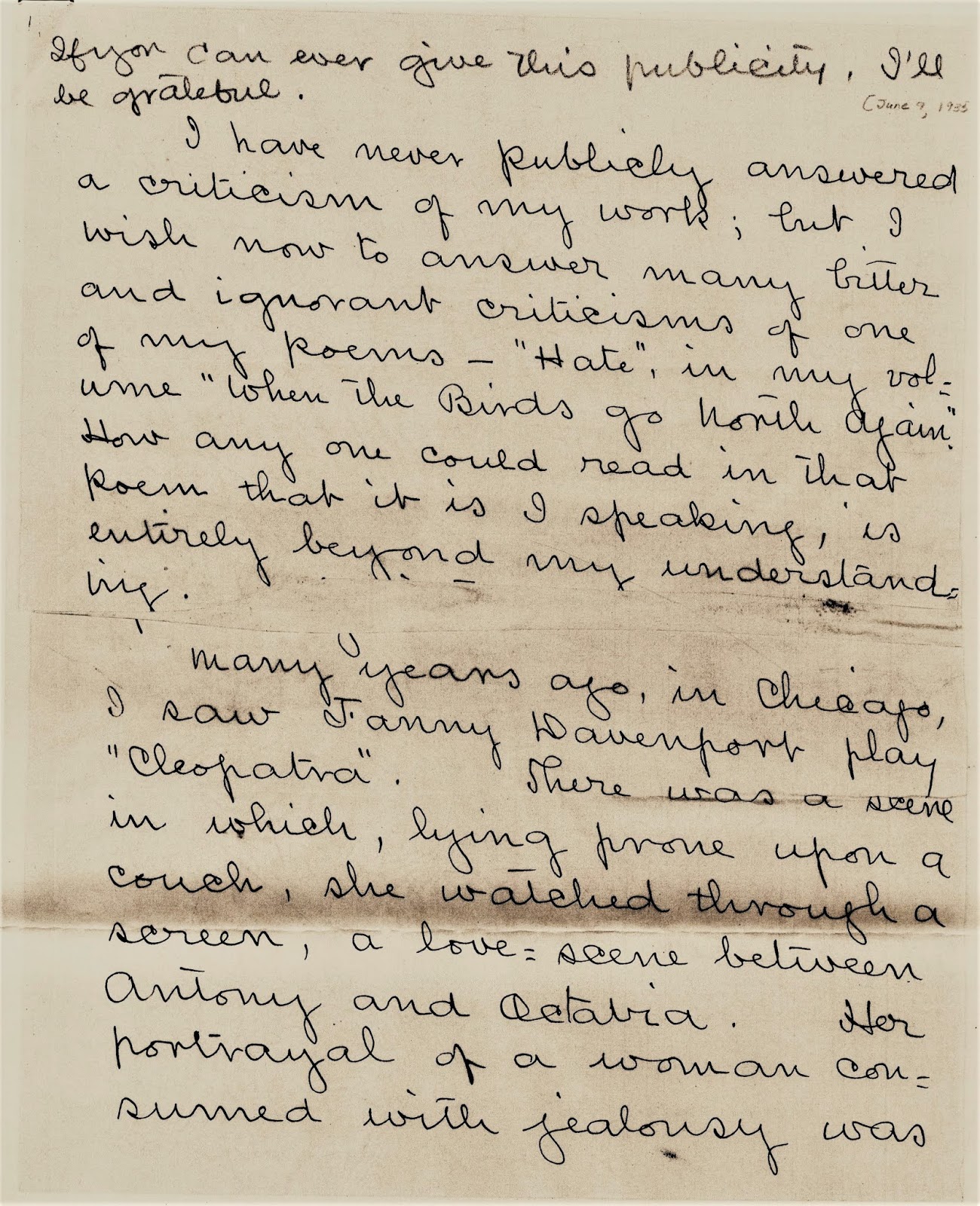

Higginson remembered this critique for decades. In a June 9, 1935 letter to Alfred Powers, she explained the origin of the poem “Hate.” (A full transcription of letter appears at the bottom of this post.)

Higginson explains that she was inspired to write the poem after seeing actress Fanny Davenport (1850-1898) in her most famous role as the Queen of Egypt in the English translation of French playwright Victorien Sardou’s Cleopatra:

Many years ago, in Chicago, I saw Fanny Davenport play “Cleopatra.” There was a scene in which, lying prone upon a couch, she watched through a screen, a love-scene between Antony and Octavia. Her portrayal of a woman consumed with jealousy was so powerful that I was deeply impressed thereby, and the poem formed itself in my mind; and upon my return to my hotel, I made the first

rough draft of it at once. It was first published under the title of “Cleopatra.”

rough draft of it at once. It was first published under the title of “Cleopatra.”

It’s unknown exactly when Higginson saw the production during a trip East coast in 1891. Once on tour, the show played at the Columbia Opera House in Chicago December 7-12, 1891, after a run first in New York City and then in Boston. Fanny Davenport produced, directed, and starred in Cleopatra. The production was proclaimed as the theatrical highlight of the year. At a cost of $50,000 (over $1.3 million today), the production had a chorus of over 120 members and used five real snakes in the performances.

Fanny Davenport as Cleopatra, New York City, December 1890.

The scene which inspired the poem was Act IV, Scene V. Cleopatra secretly listens to a conversation

between her lover Antony and the young Octavia. In the script, Antony tells Octavia how he prefers her youth and chastity to Cleopatra’s maturity and sexual experience. He compares Cleopatra to a ghost in the night and Octavia to the brilliance of the dawn. The scene leaves Cleopatra “overwhelmed” and “destroyed” and she weeps furiously before exiting the stage.

between her lover Antony and the young Octavia. In the script, Antony tells Octavia how he prefers her youth and chastity to Cleopatra’s maturity and sexual experience. He compares Cleopatra to a ghost in the night and Octavia to the brilliance of the dawn. The scene leaves Cleopatra “overwhelmed” and “destroyed” and she weeps furiously before exiting the stage.

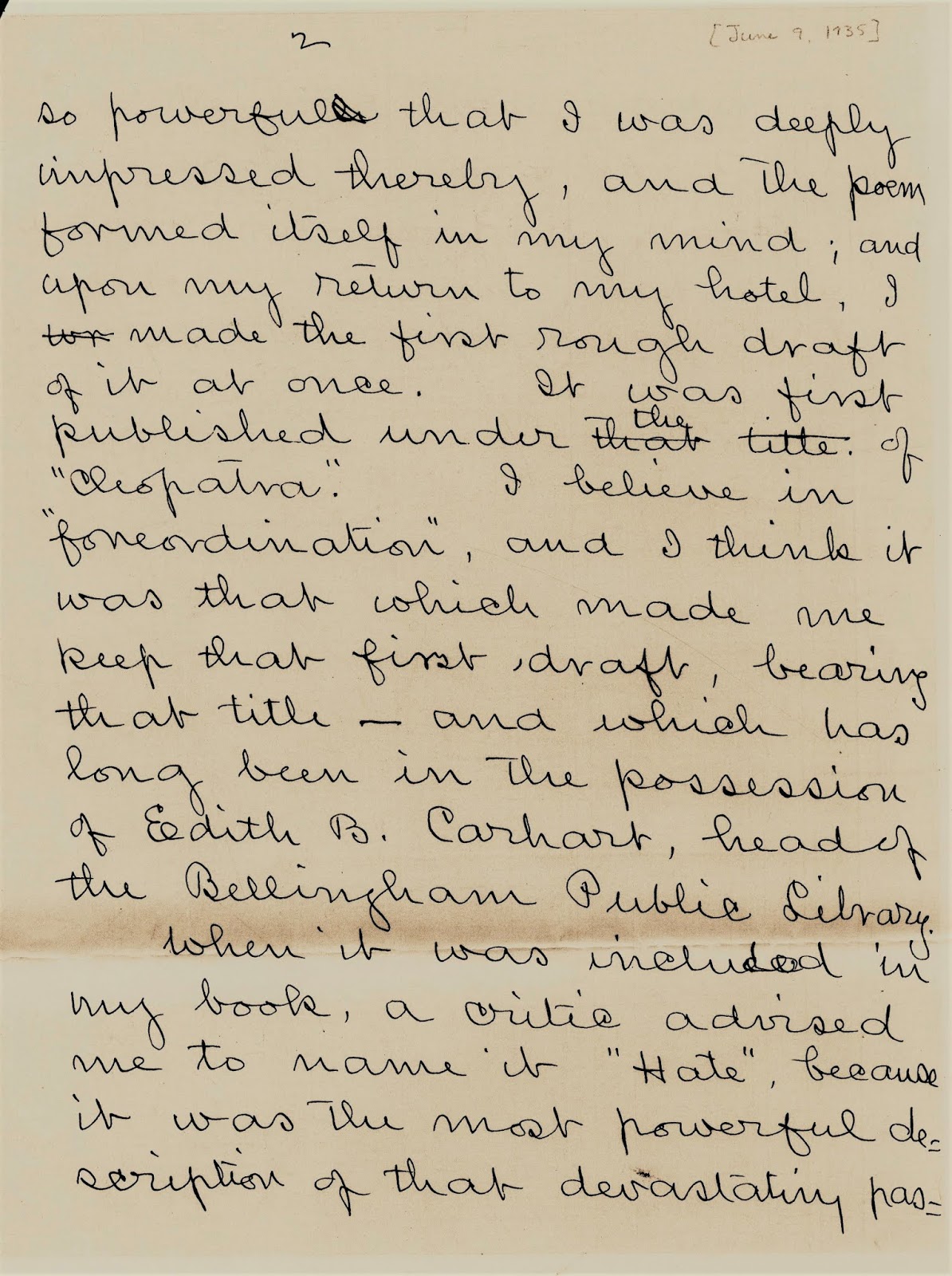

Higginson wrote, “When it was included in my book, a critic advised me to name it ‘Hate,’ because it was the most powerful description of that devastating passion he had ever read.” A draft of the poem kept in the Washington State Archives Bellingham branch contains the original title.

A draft of “Hate,” courtesy of the Ella Higginson Papers, Center for Pacific Northwest Studies, Heritage Resources, Western Washington University, Bellingham Washington.

If Higginson had retained “Cleopatra” as the title, the reviewer would not have easily confused Higginson herself with the speaker of the poem. At the close of her letter to Powers, Higginson reiterates the ignorance of the reviewer who had assumed that Higginson was writing of herself: “I wrote a ‘murder’ story once, also a ‘murder’ poem, both in the first person; but have not, as yet, been accused of that crime!”

🍀

Full transcription of letter to Alfred Powers by Ella Higginson, 9 June 1935:

If you can ever give this publicity, I’ll be grateful. I have never publicly answered a criticism of my work; but I wish now to answer many bitter and ignorant criticisms of one of my poems—”Hate,” in my volume “When the Birds Go North Again.” How any one could read in that poem that it is I speaking is entirely beyond my understanding. Many years ago, in Chicago, I saw Fanny Davenport play “Cleopatra.” There

was a scene in which, lying prone upon a couch, she watched through a screen, a love-scene between Antony and Octavia. Her portrayal of a woman consumed with jealousy was so powerful that I was deeply impressed thereby, and the poem formed itself in my mind; and upon my return to my hotel, I made the

first rough draft of it at once. It was first published under the title of “Cleopatra.” I believe in “foreordination,” and I think it was that which made me keep that first draft, bearing that title—and which has long been in the possession of Edith B. Carhart, head of the Bellingham Public Library.

was a scene in which, lying prone upon a couch, she watched through a screen, a love-scene between Antony and Octavia. Her portrayal of a woman consumed with jealousy was so powerful that I was deeply impressed thereby, and the poem formed itself in my mind; and upon my return to my hotel, I made the

first rough draft of it at once. It was first published under the title of “Cleopatra.” I believe in “foreordination,” and I think it was that which made me keep that first draft, bearing that title—and which has long been in the possession of Edith B. Carhart, head of the Bellingham Public Library.

When it was included in my book, a critic advised me to name it “Hate,” because it was the most powerful description of that devastating passion he had ever read. I wrote a “murder” story once, also a “murder” poem, both in the first person; but have not, as yet, been accused of that crime!