by Moira Stockton, Research Assistant

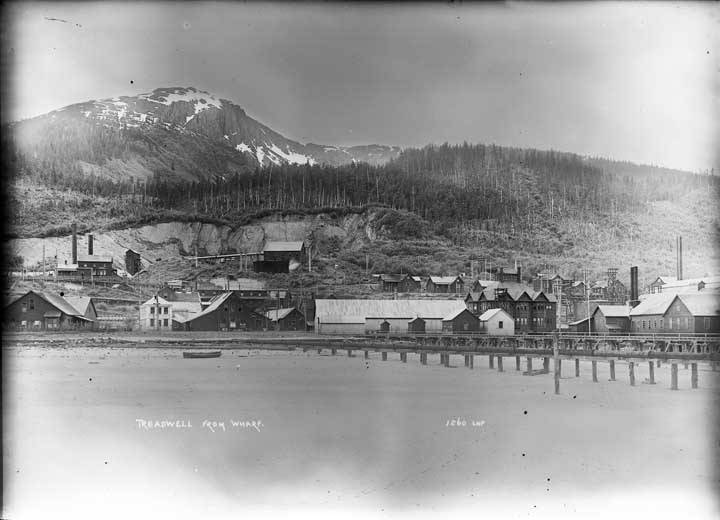

Treadwell and Gastineau Channel in 1899. Image courtesy of the Winter and Pond Collection. Photographs, 1893-1943.

ASL-PCA-87, Alaska State Library.

ASL-PCA-87, Alaska State Library.

There is a fascination in walking through these high-ceiled, brilliantly lighted stopes, and these low-ceiled, shadowy drifts. Walls and ceilings are gray quartz, glittering with gold. One is constantly compelled to turn aside for the cars of or on their way to the dumping places, where their burdens go thundering to the levels below. (Page 125 of Alaska, the Great Country by Ella Higginson, 1908)

In 1908, the prestigious Macmillan Company published Ella Higginson’s book Alaska, the Great Country. A mix of Native American cultural observations, territorial history, landscape description, and travel anecdotes, Alaska, the Great Country is a fascinating book. In the tenth chapter, Higginson recounts her experience touring America’s largest goldmine:

Our captain obtained permission to take us down into the mine. This was not so difficult as it was to elude the other passengers. At last, however, we found ourselves shut into a small room, lined with jumpers, slickers, and caps. Shades of the things we put on to go under Niagara Falls! “Get into this!” commanded the captain, holding a sticky and unclean slicker for me. “And make haste! There’s no time to waste for you to examine it. Finicky ladies don’t get two invitations into the Treadwell. Put in your arm.”

My arm went in. When an Alaskan sea captain speaks, it is to obey. Who last wore that slicker, far be it from me to discover. . . “Now put on this cap.” Then beheld mine eyes a cap that would make a Koloshian ill. “Must I put that on?” I whispered it, so the manager would not hear. “You must put this on. Take off your hat.” My hat came off, and the cap went on. It was pushed down well over my hair; down to my eyebrows in the front and down to the nape of my neck in the back.

“There!” said the captain, cheerfully. “You needn’t be afraid of anything down in the mine now.”

Alas! there was nothing in any mine, in any world, that I dreaded as I did what might be in that cap.

Treadwell opened in 1882 on Douglas Island, across the Gastineau Channel from Juneau. Between 1882 and 1922, Treadwell produced $70 million dollars in gold, just over $176 million dollars in today’s money. Accompanied by the manager of the mine (who remains unnamed in Alaska) and Higginson’s friend, Catherine Montgomery (faculty at the Washington State Normal School at Bellingham, now known as Western Washington University), they entered the Treadwell gold mine.

There were four of us, with the manager, and there was barely room on the rather dirty “lift” for us.

We stood very close together. It was dark as a dungeon.

“Now—look out!” said the manager.

As we started, I clutched somebody,—it did not matter whom. I also drew one wild and amazed breath; before I could possible let go of that on—to say nothing of drawing another—there was a bump, and we were in a level one thousand and eighty feet below the surface of the earth.

We stepped out into a brilliantly lighted station, with a high, glittering quartz ceiling. The swift descent had so affected my hearing that I could not understand a word that was spoken for

fully five minutes. None of my companions, however, complained of the same trouble.

fully five minutes. None of my companions, however, complained of the same trouble.

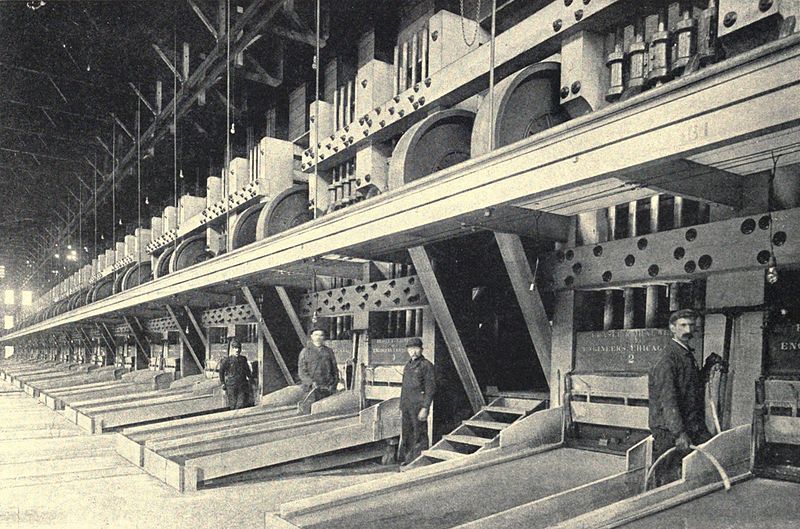

The deepest mine shaft in Treadwell was 2,400 feet below the surface. From these depths, ore (sediment containing valuable minerals or elements) was extracted and then refined in the five Treadwell stamp mills. Treadwell had the most stamps of any mining operation on the continent, housing nine-hundred stamps when Higginson toured it. Stamps are refining machines used to extract gold by crushing the ore. These gargantuan pieces of equipment endangered the lungs of the operators by constantly kicking up microscopic pieces of ore that the operators would inhale. Higginson described the noise of the stamps as

such:

such:

The nine hundred stamps drop ceaselessly, day and night, with only two holidays in a year—Christmas and the Fourth of July. The noise is ferocious. In the stamp-mill one could not

distinguish the boom of a canon, if it were fired within a distance of twenty feet, from the deep and continuous thunder of machinery.

distinguish the boom of a canon, if it were fired within a distance of twenty feet, from the deep and continuous thunder of machinery.

The stamps and operators of Treadwell in 1908. Image courtesy of Through the Yukon and Alaska, Mining and Scientific Press, San Francisco, 1909

Higginson was touring the mine for research for Alaska, the Great Country, and relentlessly questioned the manager:

No one has ever accused me of being shy in the matter of asking questions. It was the first time I had been down in one of the famous gold mines of the world, and I asked as many questions as a woman trying to rent a forty-dollar house for twenty dollars. Between shafts, stations, ore bin, crosscuts, stopes, drifts, levels, and winzes, it was less than fifteen minutes before I felt the cold moisture of despair breaking out upon my brow. Winzes proved to be the last straw. I could get a glimmering of what the other things were; but winzes!

The manager had been polite in a forced, friend-of-the-captain kind of way. He was evidently willing to answer every question once, but whenever I forgot and asked the same question twice,

he balked instantly. Exerting every particle of intelligence I possessed, I could not make out the difference between a stope and a station, except that a stope had the higher ceiling.

he balked instantly. Exerting every particle of intelligence I possessed, I could not make out the difference between a stope and a station, except that a stope had the higher ceiling.

“I have told you the difference three times already,” cried the manager, irritably.

The captain, back in the shadow, grinned sympathetically.

“Nor’-nor’-west, nor’-by-west, a-quarter-nor’,” said he, sighing. “She’ll learn your gold mine sooner than she’ll learn my compass.”

Then they both laughed. They laughed quite a while, and my disagreeable friend laughed with them. For myself, I could not see anything funny anywhere.

I finally learned, however, that a station is a place cut out for a stable or for the passage of cars, or other things requiring space; while a stope is a room carried to the level of the top of the main crosscut. It is called a stope because the ore is “stoped” out of it. But winzes! What winzes are is

still a secret of the ten-hundred-and-eighty-foot level of the Treadwell mine.

still a secret of the ten-hundred-and-eighty-foot level of the Treadwell mine.

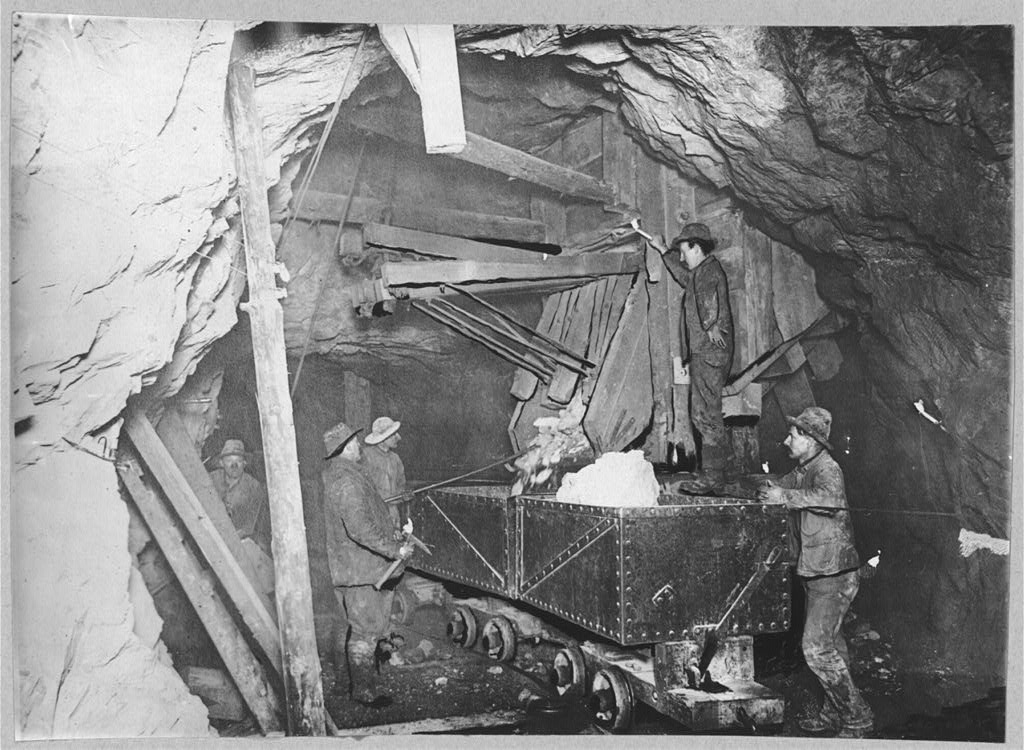

Miners work the overhead portion of stope on the 2300 ft. level in Treadwell. Image courtesy of the Harry F. Snyder Photograph Collection: Treadwell, Alaska, 1916-1918. ASL-PCA-38, Alaska State Library.

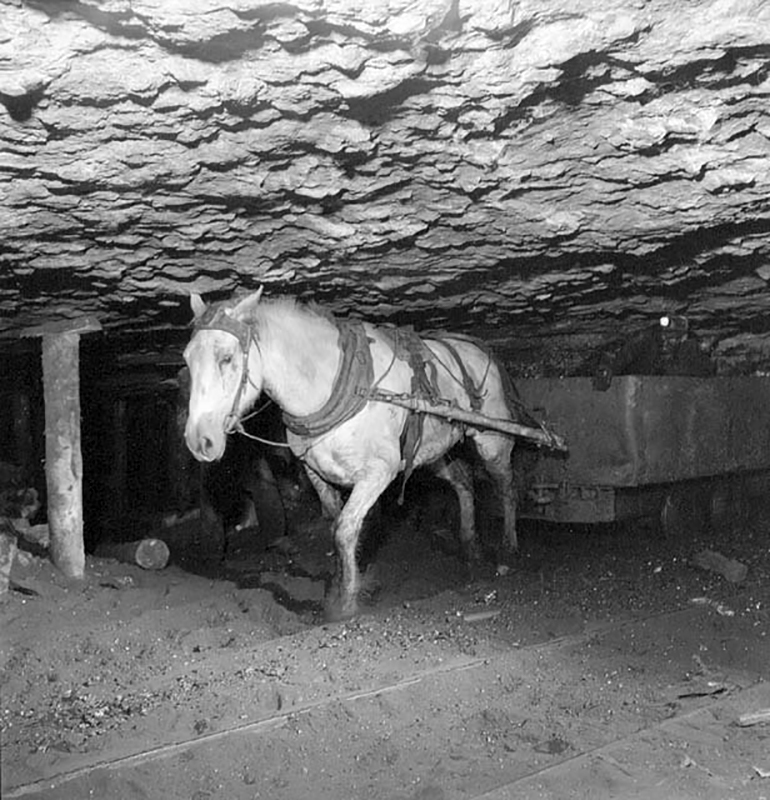

When Higginson toured Treadwell, they were still in the practice of using ‘pit ponies’ to haul tram cars of ore in the mines. Though most American mines that used equestrian labor used donkeys or mules, Treadwell followed the British method of using small horses, usually no more than twelve hands high due

to the low ceilings of the mines.

to the low ceilings of the mines.

A pit pony and miner in a mine at New Aberdeen, NS, in August 1946. Image Courtesy of National Film Board of Canada/Library & Archives Canada/PS-116676.

A pit pony being lowered into a mine. Image courtesy of “Ghosts of the Coal Mines.”

Higginson, a lover of horses herself, clearly was affected by the sight:

Tram-cars filled with ore, each drawn by a single horse, passed us in every drift—or was it in crosscuts and levels? One horse had been in the mine seven years without once seeing sunlight

or fields of green grass; without once sipping cool water from a mountain creek with quivering, sensitive lips; without once stretching his aching limbs upon the soft sod of a meadow, or racing with his fellows upon a hard road.

or fields of green grass; without once sipping cool water from a mountain creek with quivering, sensitive lips; without once stretching his aching limbs upon the soft sod of a meadow, or racing with his fellows upon a hard road.

But every man passing one of these horses gave him an affectionate pat, which was returned by a low, pathetic whinny of recognition and pleasure.

“One old fellow is a regular fool about these horses,” said the manager, observing our interest. “He’s always carrying them down armfuls of green grass, apples, sugar, and everything a horse will eat. You’d ought to hear them nicker at sight of him. If they pass him in a drift, when he hasn’t got a thing for them, they’ll nicker and nicker, and keep turning their heads to look after him. Sometimes it makes me feel queer in my throat.”

A miner and a pit pony, undated. Image courtesy of “Ghosts of the Coal Mines.”

Thanks to later innovations, horses were eventually replaced with mechanical tram cars. The last recorded group of working pit ponies was in Queensland, Australia; they were allowed to retire in 1990.

If you have read Higginson’s poetry, you are well aware of her fascination and devotion to Bellingham Bay, Puget Sound, the ocean, and most all bodies of water. It was here in the Treadwell mine that she experienced water in an entirely different way.

“I suppose,” he said, sighing, “you wouldn’t care to see the—”

I did not catch the last word, and had no notion what it was, but I instantly assured him that I would rather see it than anything in the whole mine.

His face fell.

“Really—” he began.

“Of course we’ll see it,” said the captain; we want to see everything.”

The manager’s face fell lower.

“All right,” said he, briefly, “come on!”

We had gone about twenty steps when I, who was close behind him, suddenly missed him. He was gone.

Had he fallen into a dump hole? Had he gone to atoms in a blast? I blinked into the shadows, standing motionless, but could see no sign of him.

Then his voice shouted from above me—“Come on!”

I looked up. In front of me a narrow iron ladder led upward as straight as any flag-pole, and almost as high. Where it went, and why it went, mattered not. The only thing that impressed me

was that the manger, halfway up this ladder, had commanded me to “come on.”

was that the manger, halfway up this ladder, had commanded me to “come on.”

I? to “come on!” up that perpendicular ladder whose upper end was not in sight!

But whatever might be at the top of that ladder, I had assured him that I would rather see it than anything in the whole mine. It was not for me to quail. I took firm hold of the cold and unclean rungs, and started. When we had slowly and painfully climbed to the top, we worked our way through a small, square hole and emerged into another stope, or level, and in a very dark part of it. Each man worked by the light of a single candle. They were stoping out ore and making it ready to be dumped into lower levels—from which it would finally be hoisted out of the mine in

skips.

skips.

The ceiling was so low that we could walk only in a stooping position. The laborers worked in the same position; and what with this discomfort and the insufficient light, it would seem that their

condition was unenviable. Yet their countenances denoted neither dissatisfaction nor ill-humor.

condition was unenviable. Yet their countenances denoted neither dissatisfaction nor ill-humor.

“Well,” said the manager, presently, “you can have it to say that you have been under the bay, anyhow.”

“Under the—”

“Yes; under Gastineau Channel. That’s straight. It is directly over us.”

A picture of miners in the shaft that extends beneath Gastineau Channel in 1916. Image courtesy of Frank and Frances Carpenter collection, Library of Congress.

This concluded her tour of Treadwell: “We immediately decided that we had seen enough of the great mine, and cheerfully agreed to the captain’s suggestion that we return to the ship.” It remains unknown on which trip to Alaska Higginson went to Treadwell, for she took four tours of Alaska in the years shortly before the publication of Alaska, the Great Country.

“The Treadwell is the pride of Alaska.” Higginson declares in the book. “Its poetic situation, romantic history, and admirable methods should make it the pride of America.”

Douglas Island and Treadwell as seen from Gastineau Channel, c. 1896-1913. Image courtesy of the Paul Sincic Collection. Photographs, ca. 1898-1915. ASL-PCA-75, Alaska State Library.