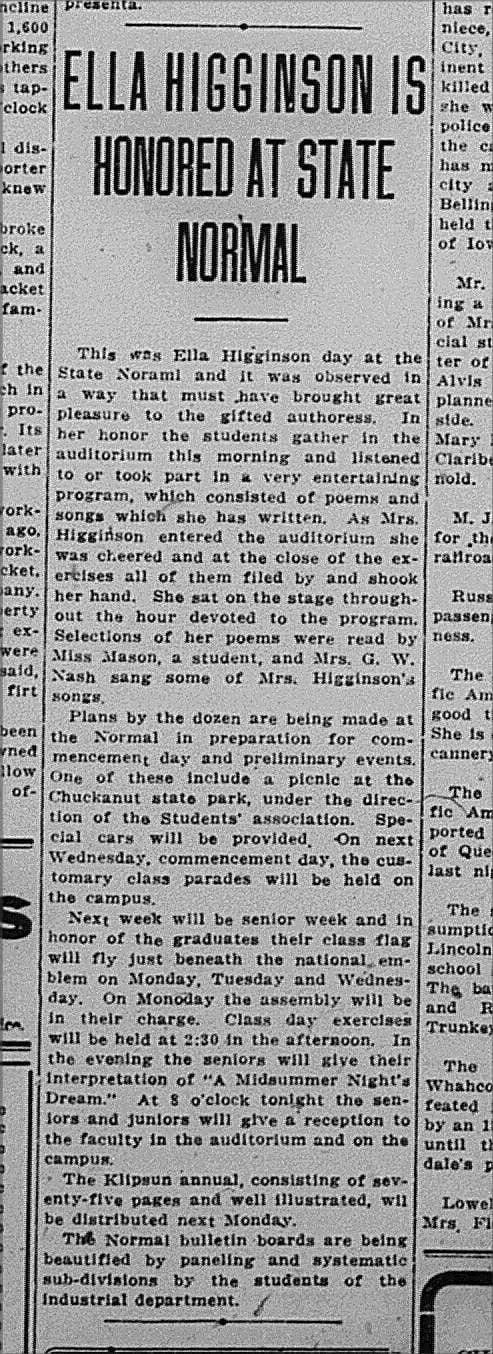

The Premier, a passenger steamer, after its deadly collision with the collier ship Willamette. Image courtesy of Wright, E.W., ed., Lewis & Dryden Marine History of the Pacific Northwest, Lewis & Dryden Printing Co., Portland, OR 1895

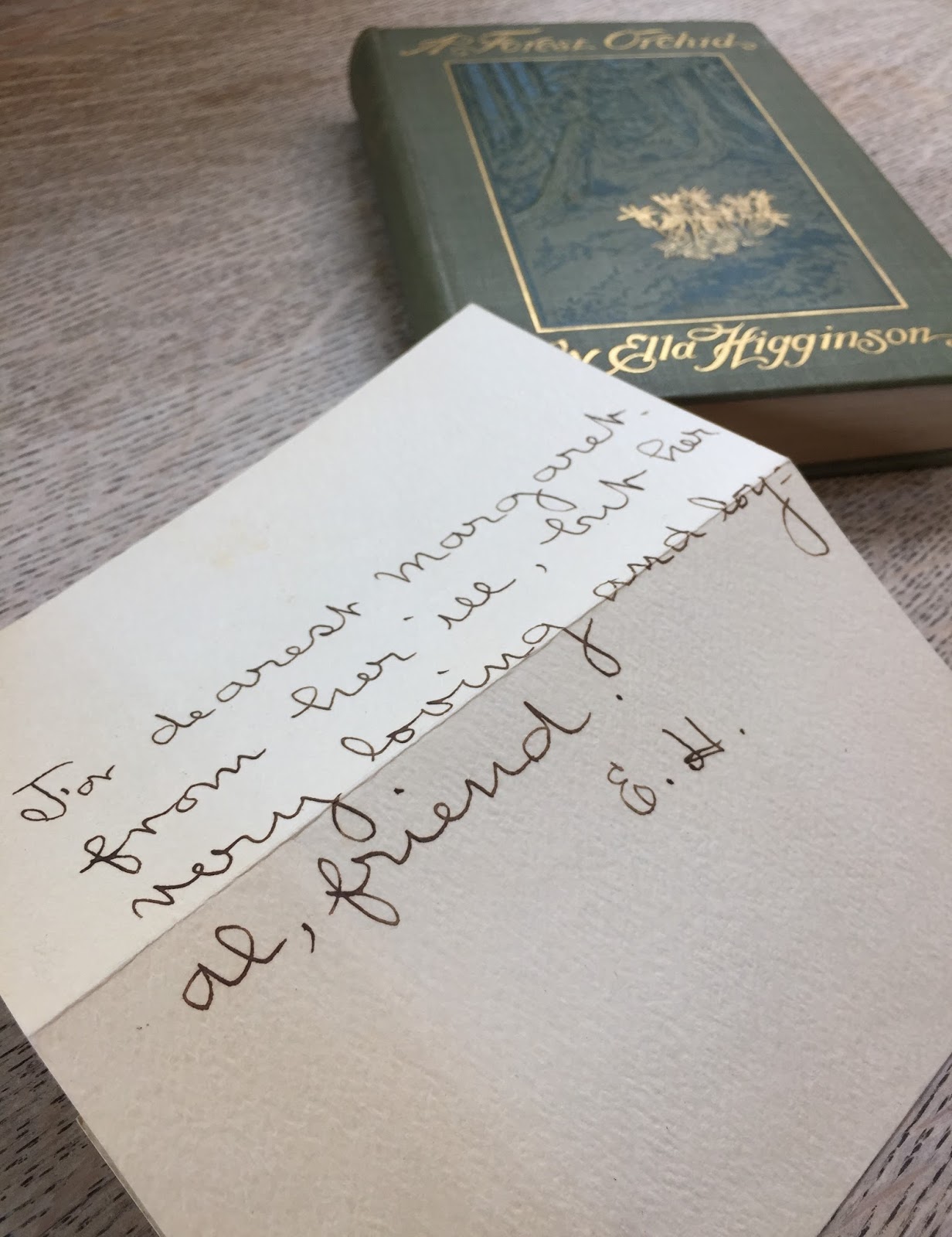

Wreck of the Premier” recounts the October 8, 1892 collision of the

collier ship the Willamette and the passenger steamer the Premier

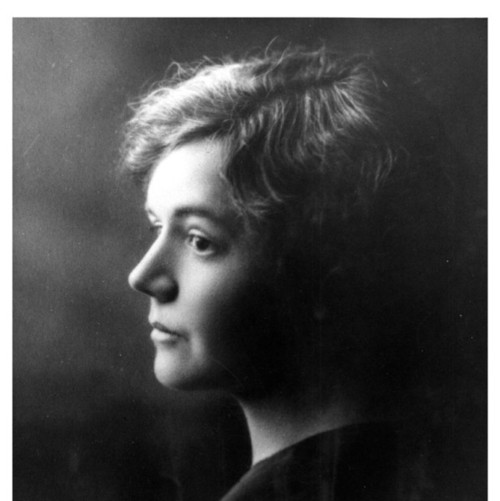

on Puget Sound that resulted in six deaths and many more injuries. Ella

Higginson, who escaped unharmed, was on the Premier heading south to

Seattle when the vessel reportedly entered a thick fog near Port Townsend. The Willamette

was carrying 2,400 tons of coal at the time, and the Premier roughly 70

passengers. Shortly after the Premier departed from Port Townsend, where

it docked briefly for passenger boarding, they were struck on their portside by

the bow of the Willamette across from Bush Point. The Willamette

impaled the Premier’s pilot house, dining room, smoking room, saloon,

and the sleeping quarters of the crew.

realized after the collision that if he were to put his vessel in reverse and

pry them apart, the Premier would immediately flood due to its gouged

portside and sink in the middle of the channel. The passengers were then

instructed to gather the dead and wounded as best they could and transport them

from the nearly-destroyed Premier to the Willamette. Captain

Hansen then plowed across the channel, driving the Premier through the

water, and beached her on Bush Point. A tugboat called the Goliah,

hauling a vessel north, passed by a little while later and was flagged down by

the Willamette. The Goliah abandoned its task and instead loaded

the passengers and raced to Seattle, where the wounded were admitted to

Providence Hospital.

Daily Chronicle of Oregon, Ella Higginson recounts her experience:

disaster which we have seen was written by Ella Higginson. She says that all

her life she has had a desire to be in an accident, preferably a water

accident, because the waves always curl up so soft and caressing that it seemed

to her it would be a good place to lie down beneath them and rest. “Well,

I have had my desire, and I am bound to confess that when I stood on the guard

of the Premier with the whole side of a bedstead in one hand, a pillow, yes a

feather pillow, in the other, my cloak under my arm, and a life-preserver

around my waist, and realized that in a moment I might be struggling with those

same waves for my life, there was nothing soft or caressing in their

appearance. I was flung on the floor several feet from my chair, and men, women

and pieces of furniture were swept violently past me. I heard groans and moans

of anguish, and low murmers of prayer, but not one scream. Not for an instance

did I lose my presence of mind.”

a life-preserver for herself, she was met with unexpected difficulty,

particularly from the other male passengers:

staterooms to get a life-preserver, but every door was locked. Then I ran out

on the rear guard, and I found men climbing down from the upper deck, and up

from the lower. They all swarmed around me, and all shouted at once, ‘Now

madam, keep cool! Don’t get excited!’ In two seconds I realized that the

flutter of a petticoat had the effect on every man of jerking his mouth open

and forcing out the words: ‘Keep cool! Don’t get excited!’ Exasperated, I

exclaimed: ‘I am cool! But in the meantime, we may as well be thinking of

life-preservers. We needn’t be too cool for that!’ ‘Life preservers!’ wildly

ejaculated a man. ‘Why, madam, we are on Puget sound! A boat can’t sink on

Puget sound!’

Even in that awful moment I was struck with the grim humor of his reply. What

an advertisement for Puget sound! Then a lady with a solemnity that puts me

into convulsions of mirth now whenever I think of it: ‘Young man, don’t you

tell us that if it ain’t so!’

chaos on board, Higginson concluded her letter by mounting her soap box and

calling for reform:

want to lift up my voice for better laws concerning life-preservers. I want

them out in plain sight, easy of access―I don’t want them under berths in

staterooms with the doors locked, I want them labeled. They may not be pretty

ornaments for finely furnished cabins, but let me tell you, Mr. Law-Makers,

that after you have been in a shipwreck, they will be beautiful in your own

eyes under any and every circumstance. Another thing, make a law that the name

of each passenger shall be taken. The man who jumped overboard is unknown, and

may always be. We don’t want to vote, but take our advice sometimes on a new

law.

from “The Premier Collision: A Visit From One of The Survivors—Ella

Higginson’s Account—Some Suggestions.” The Dalles Daily Chronicle.

25 Oct. 1892.

the Premier,” Higginson only references one specific casualty, that of

thirteen year-old Frank C. Wynkoop of Tacoma, WA who was traveling with

his family. Two places in the poem a mother is referenced, once in the first

stanza with, “One poor mute mother by her dead,” and again in the seventh

stanza with, “The mother stirred, and her pale lips/Prayed now above her dead.”

The mother here is Mrs. D. J. Wynkoop, young Frank Wynkoop’s mother, who Ella

Higginson later recalls having spoken to earlier in the voyage. Frank Wynkoop’s

head was “smashed almost to a pulp” and “Mrs. Ella Higginson, the poetess, of

New Whatcom, assisted in laying out the body of the boy” (“Disaster in

Dense Fog” The Seattle Post Intelligencer. 9 Oct. 1892).