Author Highlights of the Day:

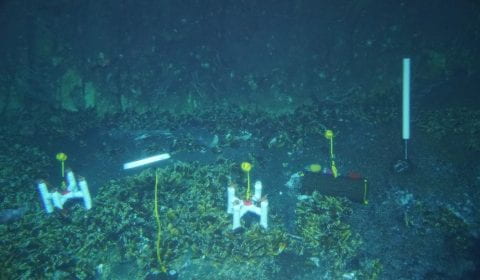

After endless hours of looking through a microscope to sort through sediment in search of mussel larval shells, we decided to take a break and enjoy the beautiful weather. While soaking up the sun on the bow we spotted a pod of dolphins riding the waves from the ship. We cheered with joy and smiled as we watched them jump over the waves as the sun illuminated a rainbow above the dolphins. Not long after we noticed them, the pod swam away despite our dolphin calls in hopes of bringing them back. We then saw some flying fish that looked like fairies as they leaped from the sea, fluttering to keep themselves above the water as they soared through the air, travelling a surprisingly long distance. These beautiful creatures entertained us while we sat in the sunlight. It was moments like this that reminded us why we love the sea so much. We lingered by the rails as long as possible, taking in the beautiful ocean view until we needed to head back to the microscopes to search for larvae. While the piles of sediment may not be as beautiful as the glistening ocean, it still is a world of its own, cluttered with shells, larvae, and eggs that are just as interesting and unique as the macrofauna that we saw from the bow. These larval shells we find will give us insight into the reproduction of these deep sea creatures by helping us to determine their location of origin and how these mussel larvae disperse throughout the ocean, and if the larvae travel from one deep sea sight to another of the sights that we visit.

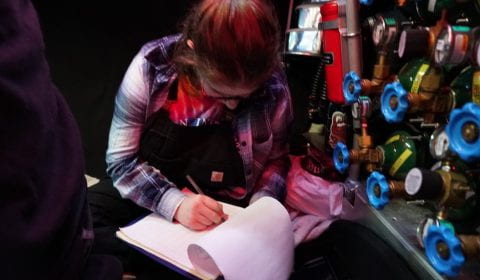

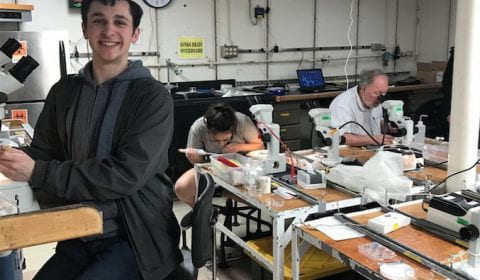

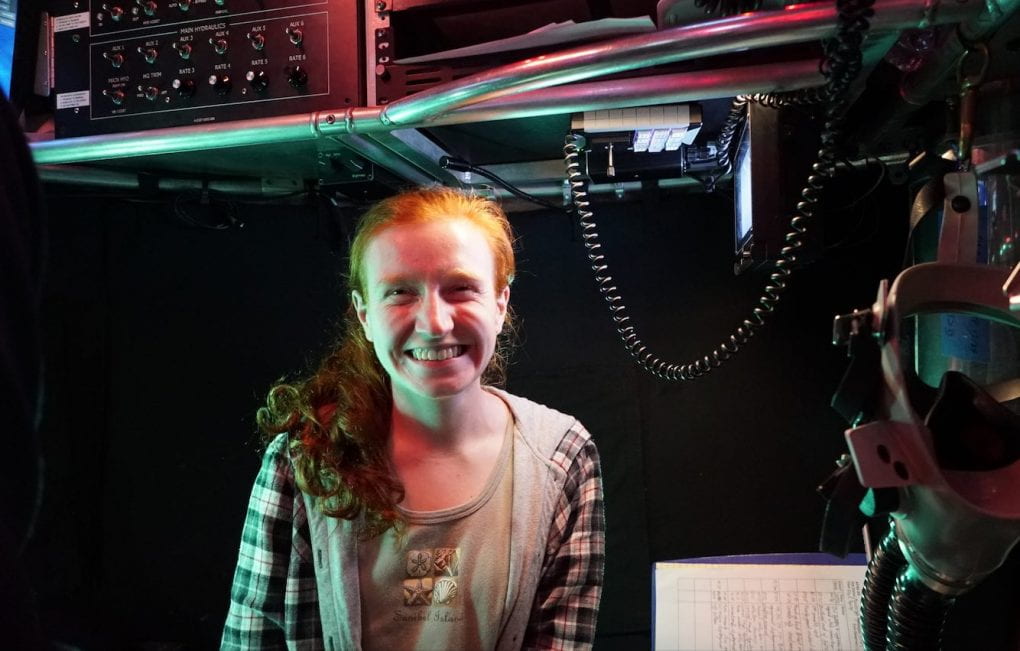

Meanwhile, the Larval Lab spent the day wrapping up projects and getting organized for the trip home. As people searched for larval shells behind us, we took especially lively larvae and photographed them under the microscopes. The abundance of individuals prevented us from naming each one of these, but they were often lovingly referred to as “lil bebes.” Additionally, Dexter and Esmeralda took final notes from their experiments with the larvae and prepped them for their journey back to Washington. Despite all the work to do, the Larval Lab still managed to make time to also enjoy the sunshine knowing full well that the weather back in Washington may not be as inviting. After dinner, both groups made sure to come together for some very important matters- group photos with Alvin, dive highlight video viewing, and an impromptu larvae remix performance of Under Pressure from Matt and Mitch. Clearly, even transit days focused on getting ready for our departure don’t fail to include larvae in some way. As this trip comes to an end for our group, we look forward to hearing updates from our graduate students about the rest of the cruise.

Methane Ice, Baby

All right, drop

Into the Gulf that glistens

Alvin’s back with a brand-new mission

Sphere of titanium, secure it tightly

His arms collect the mussels that we process nightly

Will descent ever stop?

Yo, the pilot knows.

Bioluminescence providing that glow

Depths too extreme for most species to handle

Below the photic zone, you better bring your own candles

Cameras, peering out through the gloom

Watching Lamellibranchia spawn in a plume

Methane drip, seeping through the sediment

Chemosynthetic organisms, gotta process all of it

You aren’t collecting data? Best get outta my way

As long as methane’s seepin’ we will science every day

If there was a problem, the pilot better solve it

Dove deep to get the bivalves and we don’t want to call it

Ice Ice larvae (Methane) (Methane)

Ice Ice larvae (Methane)

-Matt DePaolis, M.S. and Law student, University of Oregon