Dexter Davis, MS student at Oregon State (and former larval lab member and lifelong larval lab friend), has posted several great blogs about our expedition to his lab website. See his posts here:

Author: arellas

Postdoctoral Researcher Wanted

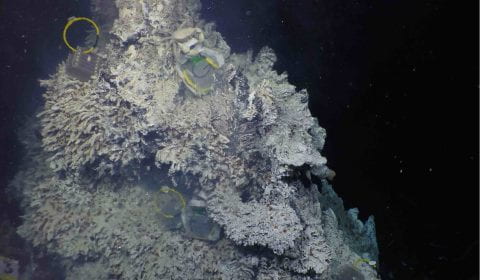

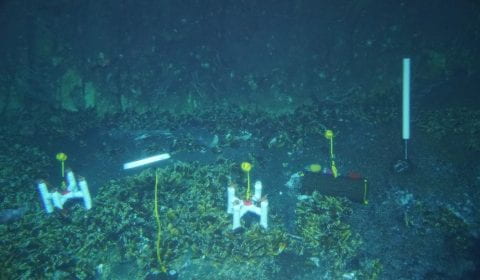

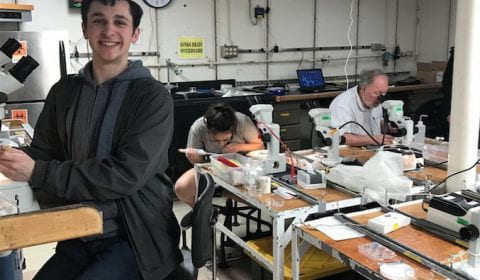

The Arellano lab is looking for a postdoctoral research associate to work on an NSF-funded collaborative project investigating “The Predictive Nature of Microbial Biofilms for Cuing Larval Settlement at Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vents.” The postdoc will work with PI Dr. Shawn Arellano and collaborators at Rutgers and Woods Hole Oceanographic using manipulative field experiments at the East Pacific Rise hydrothermal vents to model the habitat and biofilm cues that predict variations in larval settlement. Field experiments will be followed by shipboard tests of hypotheses using field collected larvae, lab developed biofilms, and pressure vessels. Because WWU is a primarily undergraduate institution, there are also opportunities to work with undergrads and MS students, and potentially to teach and participate in pedagogical workshops.

The successful candidate will be a marine ecologist with strong experimental design and quantitative skills, as well as interest or knowledge in larval settlement and hydrothermal vents. Prior seagoing experience is not required but is a plus. The position is a two-year appointment and our first research cruise is winter 2022. Someone who could start by Fall 2021 is preferred.

Position Duties and Responsibilities:

- Conducting experiments at sea, managing data, and conducting statistical analyses (50%)

- Writing manuscripts for submission to peer-reviewed journals; presenting data at scientific conferences. (25%)

- Broader impact activities: mentorship of undergraduates and graduate students and participation in a science-in-action film (15%)

- Preparing for research cruises, including ordering, preparing equipment, packing, and shipping (10%)

The successful candidate must be willing and able to conduct research at sea for long periods of time (1-2 months at a time, on at least two research cruises).

Master’s Students Wanted

Master’s students wanted! I will be taking 1-2 new graduate students to work on either of my projects associated with symbiont-larval interactions at hydrothermal vents. You may read more about those projects here. In the larval lab, we particularly value diversity and providing excellent experiences to help you reach your goals. And most of all, you must be excited about larvae!

New SALT project website

Arellano Lab featured in a Western Today article

News from our Dec 2019 EPR cruise

Our work at the EPR was featured on the ‘Extreme Field Work’ feature of Gizmodo: https://earther.gizmodo.com/it-really-is-otherworldly-what-it-s-like-to-visit-th-1844305760

Last day of Leg 1

Author Highlights of the Day:

After endless hours of looking through a microscope to sort through sediment in search of mussel larval shells, we decided to take a break and enjoy the beautiful weather. While soaking up the sun on the bow we spotted a pod of dolphins riding the waves from the ship. We cheered with joy and smiled as we watched them jump over the waves as the sun illuminated a rainbow above the dolphins. Not long after we noticed them, the pod swam away despite our dolphin calls in hopes of bringing them back. We then saw some flying fish that looked like fairies as they leaped from the sea, fluttering to keep themselves above the water as they soared through the air, travelling a surprisingly long distance. These beautiful creatures entertained us while we sat in the sunlight. It was moments like this that reminded us why we love the sea so much. We lingered by the rails as long as possible, taking in the beautiful ocean view until we needed to head back to the microscopes to search for larvae. While the piles of sediment may not be as beautiful as the glistening ocean, it still is a world of its own, cluttered with shells, larvae, and eggs that are just as interesting and unique as the macrofauna that we saw from the bow. These larval shells we find will give us insight into the reproduction of these deep sea creatures by helping us to determine their location of origin and how these mussel larvae disperse throughout the ocean, and if the larvae travel from one deep sea sight to another of the sights that we visit.

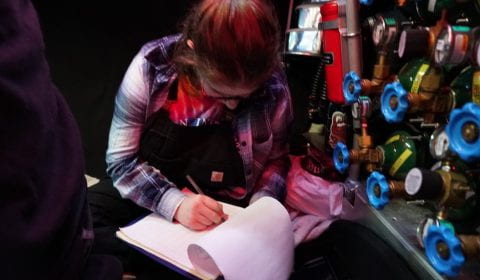

Meanwhile, the Larval Lab spent the day wrapping up projects and getting organized for the trip home. As people searched for larval shells behind us, we took especially lively larvae and photographed them under the microscopes. The abundance of individuals prevented us from naming each one of these, but they were often lovingly referred to as “lil bebes.” Additionally, Dexter and Esmeralda took final notes from their experiments with the larvae and prepped them for their journey back to Washington. Despite all the work to do, the Larval Lab still managed to make time to also enjoy the sunshine knowing full well that the weather back in Washington may not be as inviting. After dinner, both groups made sure to come together for some very important matters- group photos with Alvin, dive highlight video viewing, and an impromptu larvae remix performance of Under Pressure from Matt and Mitch. Clearly, even transit days focused on getting ready for our departure don’t fail to include larvae in some way. As this trip comes to an end for our group, we look forward to hearing updates from our graduate students about the rest of the cruise.

Methane Ice, Baby

All right, drop

Into the Gulf that glistens

Alvin’s back with a brand-new mission

Sphere of titanium, secure it tightly

His arms collect the mussels that we process nightly

Will descent ever stop?

Yo, the pilot knows.

Bioluminescence providing that glow

Depths too extreme for most species to handle

Below the photic zone, you better bring your own candles

Cameras, peering out through the gloom

Watching Lamellibranchia spawn in a plume

Methane drip, seeping through the sediment

Chemosynthetic organisms, gotta process all of it

You aren’t collecting data? Best get outta my way

As long as methane’s seepin’ we will science every day

If there was a problem, the pilot better solve it

Dove deep to get the bivalves and we don’t want to call it

Ice Ice larvae (Methane) (Methane)

Ice Ice larvae (Methane)

-Matt DePaolis, M.S. and Law student, University of Oregon

Final Dive in the Gulf of Mexico

We live in a world where we can visualize virtually anything through the use of technology and word-of-mouth. Places you haven’t visited can be 360-toured through Google and legends get told by word-of-mouth globally and have been for millennia. Life at sea, despite having limited internet connection, is a part of this world as well. The instant I set out on this journey I was told stories of previous dives in ALVIN and what life is like at the bottom of the ocean. Tales varied from rock structures that looked like giant skeletons to Humboldt squids swimming right up to the windows. Every story that was told I desperately wanted to believe, however, like most people, I am a believe it when I see it kind of person.

Today was my chance to believe it all. When I found out I was getting an ALVIN dive I was overcome with emotions, but most of all excitement. I became more excited when I found out I was going to dive at our last (and deepest) site in the Gulf of Mexico and the first place cold seeps were ever discovered: the Florida Escarpment. The day started out normally, except today I was greeted by smiling faces and people asking, “Are you ready?” or “Are you excited?” I got into ALVIN feeling surprisingly normal and ready to begin descending. It wasn’t until the sub hit the water that I became really excited and the gravity of the situation truly hit me. In an instant, a brilliant blue washes over all five windows and you are engulfed into a world so unlike our own on land. Throughout the entire 3200 meters down, bioluminescent plankton floated by like fireflies. This in combination with the technology inside the sub made me feel like Luke Skywalker in the Millennium Falcon.

The bottom came into view and the work began. The dive went smoothly; all traps were deployed and all organisms that were needed were collected. However, the work didn’t take away from the magic of this unique site. The site sloped up to a looming giant carbonate wall. All along the slope were countless mussel beds, tube worm bushes, bacterial mats, lobsters, shrimp, clams, and chunks of carbonate. The bacterial mats created depth to the flat surface by adding streaks of white, copper, black, and dark green all over the slope. When we settled into our deployment site, a beautiful (and adorable) lavender octopus was seen relaxing on a nearby mussel bed. This was the highlight of the dive for me because it was an incredibly stunning creature and we were able to capture fantastic footage of it.

By the end of the dive, I fully believed every story I had been told about ALVIN dives and life at the bottom of the ocean. The environment down there feels like an entirely different planet. The giant rock structures mixed with the complex community of organisms creates a unique biome unlike anywhere else on the planet. If I could, I would dive every day and explore everything our oceans’ depths have to offer. As much as I try my best to explain its beautiful magic, it really is an experience you need to see to truly believe.

Environmental Note:

Although the deep was breathtaking in every way, there were still clear evidence of human contamination. I’m not talking scientific dive labels or sediment disturbance created by the sub. Instead, there were several places where we observed trash stuck to organisms or floating along the bottom current. I personally witnessed fine net mesh stuck to mussels and a plastic cup drifting through the environment. Even over 3000 meters down, the ocean still feels our negative influence on the planet. Its for this reason that I will always encourage the reduction of plastic use and implementation of better fishing practices especially with trash and fishing nets.

Chitons and mussels and crabs, oh my!

Today is a transit day on the Atlantis to our last site, The Florida Escarpment. Most everyone took advantage of the late start to sleep in, since when Alvin dives we need to wake up at around 7am. While the normal daily processes continue, many of the Western students are working on their personal projects. Though Alvin dives into the deep to collects samples, the processing and investigations happen here all day on the Atlantis.

Dexter and Esmeralda for the past week have been staring through microscopes all day to find larvae. This has led them to be curious about what deep sea mussels prefer to settle on. In order to answer this they are testing to see if they settle more on adult mussel shells, juvenile mussel shells, carbonate rocks, byssal threads, or the plastic of the petri dish. They are doing these experiments in both filtered sea water and the water mussels have been living in to see if mussels release chemicals that influence settling. This will help us better collect larvae samples in the future and understand where mussels are found in the deep-sea. “It’s been really fun looking through microscopes. There’s a bunch of things that you don’t necessarily care about at first, but then you see there’s a lot of fun things you get to see that live in the dark,” reports Esmeralda Farias, senior at WWU.

Hailey Dearing, a second year undergrad at WWU, is interested in possibly carnivorous snails. She will be giving the snail a variety of food including worms, mussels and shrimp to see if the snail shows a preference. There is little information on this snail, including its prey, so she will be contributing largely to the understanding of this organism. Hailey notes, “I’m really grateful to be participating in this sort of research as an undergrad.”

My work on the boat has mainly consisted of looking at videos taken by Alvin at every dive spot, which I feel so lucky to do. I am also a part of the group that takes the organisms out of the Bio-box on Alvin after each dive and put them into chilled seawater. It’s amazing to watch videos of the deep sea and then realize that for every sample we collect, I am the first person to see and hold the organisms in my own hands. After the organisms are collected, they are sorted and the bottom of the biobox is sieved to collect anything we missed. Mussels are shucked, tubeworms are spawned, larvae are identified, and the equipment is modified for the next dive. Additionally, I am working on the animal behavior of snot worms. At the sites where we found them, the worms were in large clumps together, so I will be studying their movement patterns to find each other and how they behave as individuals vs. in groups.

Author’s Highlights:

Adieu, soleil

Landlocked in Montana as a child, but craving the majesty and mystery of the ocean, I had no choice but to read of the high seas. For years, I sailed aboard the Nautilus with Dr. Aronnax and avidly flipped through marine textbooks. One day, I happened upon a book with a single page describing cryptic deep-sea coral habitats and I was entranced; a hidden beauty in the ocean that only Captain Nemo could find in his submersible. Yet today I said goodbye to the sun much like Captain Nemo by dipping beneath the waves in the HOV Alvin.

As a student working in Dr. Shawn Arellano’s lab, I’ve been excitedly anticipating our cruise for several months. However, I never expected to go in a submarine! The preparation for today’s dive began late last night when all the students on board decided to decorate Styrofoam cups. We each sent a Styrofoam cup down to be shrunk by the pressure of the ocean. During the evening, I participated in the age-old tradition of avoiding liquids due to the lack of restrooms on the small sub.

Waking up in the morning brought a fresh wave of excitement as I donned all cotton clothing (any synthetic fibers are a flammable hazard inAlvin). My next step was to simply step into the sub and descend into the deep! Though I didn’t quite travel 20,000 leagues like Captain Nemo, I did get to go down 1,093 meters which is our deepest dive thus far. As soon as we hit bottom, we began a search for beds of the cold seep mussels we need for our research. Within minutes of starting our exploration, I suddenly noticed a large crimson squid drifting by the submarine!

The excitement continued as I saw starfish scattered on the sea floor and jellyfish floating by me. During our search, I looked out the window and suddenly saw a couple of deep-sea corals peeking out from behind a ridge. I gasped in excitement to be just feet from an organism I fell in love with as a child. The sub pilot moved us along until we found a large enough bed of mussels where we could collect organisms and deploy equipment. The weather that we were oblivious to in the depths unfortunately took a turn for the worst at the surface so we had to return to the ship a bit early. Luckily, we awaited a warm (or perhaps I should say cold) welcome where I got to participate in the tradition of getting a bucket of ice water dumped over my head immediately following my very first Alvin dive!