Dr. Tanika Ladd is what I would call a Swiss Army Knife scientist; that is to say, she has more than one tool in her methodology tool belt. With a background not typically seen in marine ecologists, she brings a refreshing perspective to the world of marine larval ecology and demonstrates what it truly means to be a collaborative, interdisciplinary scientist.

While most marine biologists earn their degrees in various types of biology, Dr. Ladd took a different approach. Earning her Bachelor’s degree in Mathematics, with minors in environmental science, chemistry, and physics, she started off her career in marine science with an incredibly dynamic foundation. After earning these degrees from Western Washington University, Dr. Ladd dove headfirst into a PhD in Marine Science at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Here, she shifted her focus to biological oceanography and loved implementing techniques from her different areas of expertise.

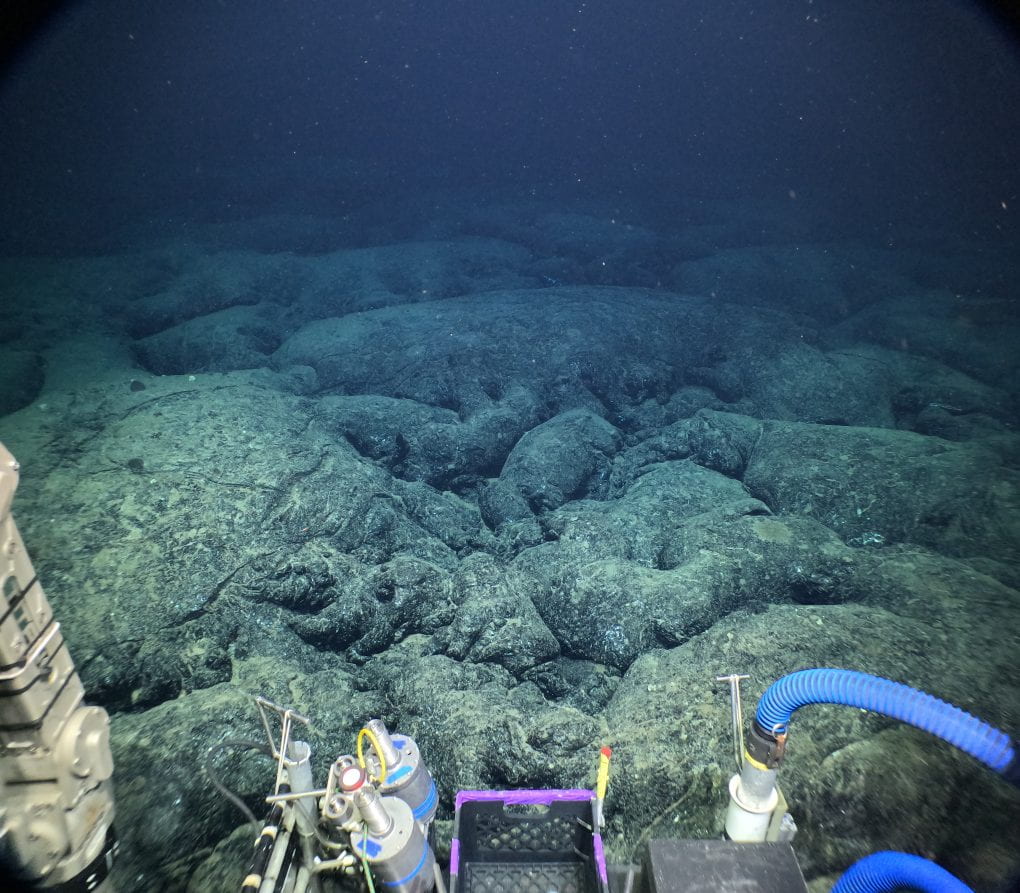

Now, Dr. Ladd has spent the last three years working as a postdoctoral researcher in the Larval Lab, where she specializes in the communities of larvae at deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Specifically, at the East Pacific Rise (EPR). When asked about the decision to pivot into the realm of larval biology, Tanika admits she was really excited to join the lab but wasn’t fully sure what to expect. Still, Ladd found the complexities of biology fascinating, noting, “[in math] you come up with this number, and that’s your answer. I learned that biology was sort of interesting because there’s a lot of the time, not [simple] answers.” Ladd, however, aspires to “figure out answers to unanswerable questions or [at least] really complex questions… that’s what brought [her] to biology.”

This and, of course, the leader of The Larval Lab: Dr. Shawn Arellano, who recognized Ladd’s skillset and invited her to work as a postdoctoral researcher on the “EPR Biofilms 4 Larvae” project funded by the National Science Foundation. Together, Ladd and Arellano work as part of an ongoing collaboration with scientists from Rutgers University and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to investigate how deep-sea larvae find their place to settle.

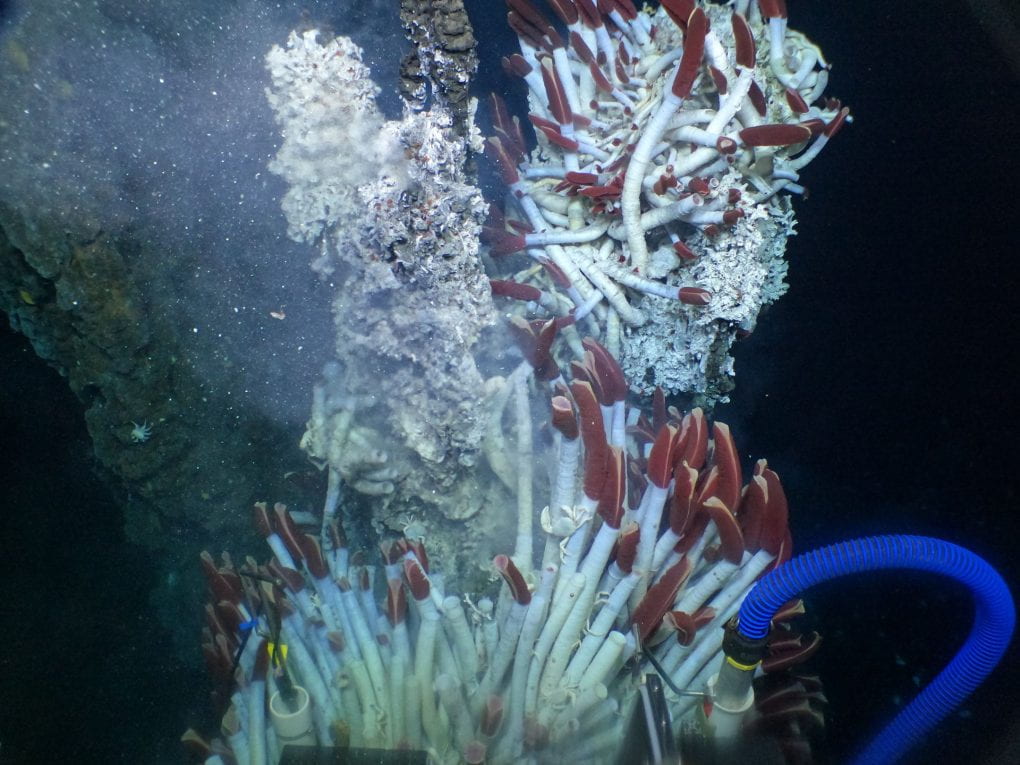

To understand the motivation behind this work, let’s walk-through an example. To start, “larvae” (singular “larva”) is just another word for “babies.” However, you may be surprised to know that these babies look and act very different from their parents. For example, if you are the larva of the hydrothermal vent mussel Bathymodiolus thermophilus, your parents probably don’t move around much. They stay put at a nice, cozy distance away from their home chimney. As Ladd puts it, “animals that live near hydrothermal vents have these really specific conditions that they have to live in for their survival,” so as a grown-up mussel, you stay where the conditions are right. However, in a constantly changing environment, like at a hydrothermal vent, your parents’ neighborhood may not stay home-y for long! Because of this, adults usually release their babies to go find a new place to live.

If your adult form doesn’t move around much, however, how do they find these specific conditions needed for survival? Enter: the “planktonic larval phase.” Basically, during this phase of life, larvae get to search for their own place to call home while swimming or floating in the water (mostly they just go with the flow). But, just like an angsty teenager outgrows their rebellious phase, larvae too must outgrow their nomad phase. When they find the right spot, larvae metamorphose (transform) into a settled juvenile and ‘put down roots,’ so to speak.

The deep sea is a massive space though, so you might be wondering… how do these larvae know where to land? This is exactly the question Dr. Tanika Ladd has been investigating. As Ladd puts it, scientists don’t “really know about what actually tells [larvae], ‘hey, this is a good place for you to settle!’” Well… until now.

In the recently published paper Faunal colonists, including mussel settlers, respond to microbial biofilms at deep-sea hydrothermal vents (Ladd et al., 2024), Ladd and collaborators investigated the role of biofilms in attracting animal settlers, including larvae. Biofilms (communities of bacteria and microbes) coat surfaces at hydrothermal vents and integrate information about environmental conditions that may be the green light for larval babies looking to land. Ladd explained further, saying these biofilms form in a “dynamic environment where sometimes the temperature can go up really high, sometimes it’s super low, sometimes there’s a bunch of hydrogen sulfide [a really important chemical in the deep-sea], sometimes there’s not.” These changes in environmental conditions impact which bacteria and microbes form the microbial biofilm, and Ladd states:

There may be different communities associated with those established biofilm surfaces… [we] found that the foundational mussel species, Bathymodiolus thermophilus, that lives at hydrothermal vents at the East Pacific rise, does seem to preferentially settle on established biofilm surfaces… So it’s likely that this larva is responding to some cues based on those biofilms, and not just the chemical and physical conditions of the vent itself.

Additionally, the team found that these biofilms seem to impact not just larvae, but other faunal (animal) communities as well. This is an incredibly promising finding, and Ladd’s contribution to this work will enhance our understanding of how communities of life function at hydrothermal vents. Still, this paper is just the tip of the proverbial iceberg, especially when it comes to deep-sea larval settlement. While Ladd’s paper suggests that biofilms may be important cues for mussel babies to find their new home, the next step is to expand their investigation to include other larvae.

While colleagues focus on characteristics of the biofilms themselves, Tanika remains hard at work identifying the larvae they collected. Her tools of choice? Microscopy (using a microscope to look at the minuscule larvae) and confirming these identities with a genetic technique called “barcoding”. (Think of the barcode on a bag of chips that tells the register what item you’re buying… but instead of black rectangles, it’s DNA, and instead of chips, you’re discovering whose baby you’re looking at!) To recap: Step 1: Sort the babies by looks. Step 2: Scan their DNA to confirm. Sounds simple enough, right? Well, maybe not. Identifying babies smaller than the eye can see comes with many challenges, especially when they look nothing like mom or dad. Ladd reflects on the difficulties, saying, “I had never seen any of these [larvae] before for the most part… [it] was a learning curve for me figuring out just how to identify things, [and] how to count them accurately.”

Not only has Dr. Ladd become a powerhouse larval sorter herself, but she’s created several photographic guides to help other scientists with identification of these deep-sea babies. This in and of itself is another huge accomplishment. As Ladd noted, there is a huge information gap when it comes to identifying deep-sea larvae.

These days, Ladd remains hard at work, fiendishly pouring over plates of larvae to collect and document as many of them as possible. Working diligently towards the next discovery surrounding the interactions between biofilms and larvae at hydrothermal vents. Despite the long hours at the microscope, though, Ladd loves it. When asked about her plans after The Larval Lab, Dr. Ladd noted that she is fascinated by how life exists in extreme places, and she wants to continue working in deep-sea science. She stated,

This is what I should have done all along… The entire world is connected by our oceans, and we need to understand how the ocean works in order to explain things like the global climate. [The deep-sea is] not a place that we think about on a normal everyday basis, [and] we could understand it a lot better than we do… there are just so many complex factors at play that it just takes a lot of effort for people to understand it… [but] I can’t imagine myself doing anything else.

EPR Biofilms4Larvae project is a multi-institutional NSF grant: OCE-1948580 (Arellano), OCE-1947735 (Mullineaux), OCE-1948623 (Vetriani).

Also find us on Instagram! @larvallab, #Biofilms4Larvae